The central thesis of game management is this: Game can be restored by the creative use of the same tools which have heretofore destroyed it—axe, plow, cow, fire, and gun.

—Aldo Leopold, from the foreword to Game Management (1933)

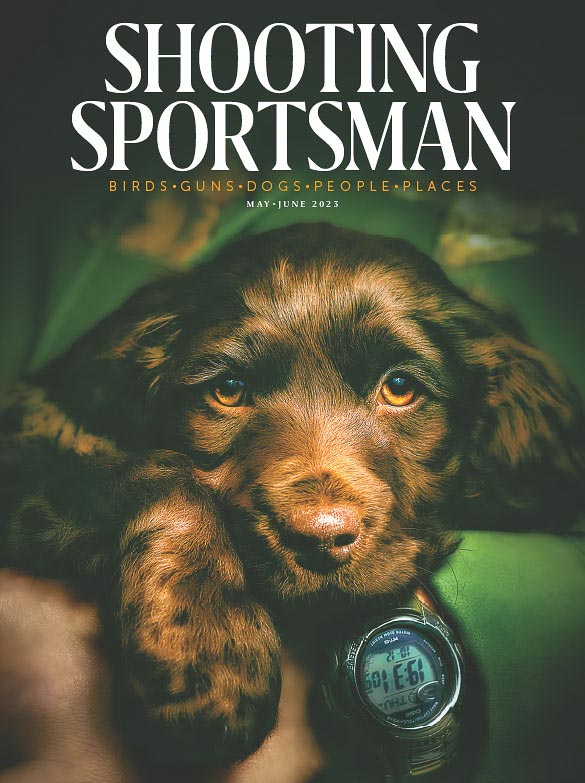

Each evening the pup and I walk around our modest little 40 acres. While he uses his nose, my eyes scan the habitat as I listen for an especially strong snuffle, which is usually followed by a burst of grouse or woodcock wings. When we get to the creek, I sit for a few minutes hoping a wood duck or two fly by.

The trick I’m faced with is maintaining habitat for scores of species on our acres. Wood ducks and pileated woodpeckers need mature trees large enough for nesting cavities. Our largest oaks rain down acorns every fall for the benefit of wood ducks, ruffed grouse, turkeys and deer. Dense stands of aspen saplings provide habitat for ruffed grouse, woodcock and golden-winged warblers.

Walking these woods every day tells me where the birds are. However, maintaining this diversity and abundance of wildlife takes more than walking and watching. It takes work.

At our scale, it’s primarily about cutting firewood. Some areas we just don’t cut. In some areas our cutting is selective. In other areas we clearcut everything. When the snow melts, our aspen clearcuts are a mess. By the time the snow flies, there will be dense stands of aspen stems over my head. The following summer I’ll look for young broods of woodcock and grouse.

The thickets of aspen provide virtual fortresses against predators and weather. Insects are attracted to these warm, sunny areas. These acres also are flush with raspberries, chokecherries and other fruits. All are valuable food sources during the summer.

If we had just a few more acres, we’d have enough for a commercial timber sale and harvest. We could make money and create wildlife habitat at the same time. It’s incredibly rewarding to hear golden-winged warblers bee-bz-bz-bzing, woodcock peenting and grouse drumming in areas we cut recently. Of course, those who own larger tracts and managers with local, state and federal agencies are doing the same thing on much greater scales.

The same basic principles of working forests apply in grasslands. In my former job, April mornings found us driving gravel roads listening for the booming of prairie chickens. We focused on grazed pastures. The males want to be as visible as possible to attract females, and they need short grass to do that. It wasn’t unusual to see and hear crowing rooster pheasants in the same general habitats—selecting areas where they could be both seen and heard.

In the next month hens would disappear into the taller ungrazed or lightly grazed grass for nesting. Some studies have shown that light grazing improves nest survival for blue-winged teal and presumably other birds. Tall, ungrazed grass provides cover for nest predators like skunks, raccoons and foxes. Light grazing removes enough cover to expose these predators but still provides enough cover to hide nests, eggs and hens.

In his 1946 classic Woodcock, J.A. Knight states that woodcock prefer pastures where the grass is four to five inches high, because taller grass “does not present enough freedom of movement,” while “short grass fails to provide enough cover.”

Once they hatch, grouse, quail and pheasant chicks often seek shorter grass where it’s easier for them to move around. A 2010 study concluded that both pheasant and quail chicks have higher feeding rates in cover that includes “more open space at ground level.” The patchy structure that light grazing creates opens areas where it’s easy to move around but leaves taller cover nearby for birds to escape into at a moment’s notice. The paths left by the cows help young and adult birds move around the prairie. Studies have shown that duck broods often follow cow paths from nests to wetlands instead of taking the most direct route to water.

Cattle primarily eat grasses, and this creates more room for wildflowers. A greater diversity and abundance of wildflowers attract more insects. The grazed grasses attract grasshoppers, which feed on the succulent regrowth. I clearly remember several summer days on some carefully grazed pastures where the buzz of insects was louder than the meadowlarks and the prairie winds.

Cow pies quickly fill with insect eggs and larvae. A close inspection will show where gamebird toes have scratched and beaks have pecked or where holes have been left by probing snipe and woodcock. This is yielding good protein for fast-growing chicks.

There are many areas that are so sensitive that you rarely or never hear the roar of a chainsaw or see a cow’s hoofprint. Some forests would take millennia to recover from logging, and some habitats might take a century to recover from grazing. However, where appropriate, logging and grazing can provide the ecological disturbances that the areas need to create and maintain habitat diversity and wildlife productivity.

The key with any management is having a little of everything on the landscape. Some forest-wildlife species need young, regenerating forests while others need mature forest. At different stages of life or times of year, grassland birds need a range of short, medium and tall vegetation. The question is what ratio and patterns of those different grass heights and forest structures on the landscape are most beneficial.

State wildlife agencies, the US Fish and Wildlife Service and many conservation organizations have online resources and/or books that provide both the scientific background of habitat management and the practical how-to advice for particular regions. Often they have staff who can visit a property and offer specific advice.

Are there still areas with unsustainable logging and overgrazing? Absolutely. However, it doesn’t have to be that way. One 1976 study concluded that woodcock numbers will “ebb and flow with the fortunes of the pulpwood market.” In 1953 Kansas researchers concluded that the “most profitable” long-term use of pastures was also beneficial to prairie chickens. A 2001 study from Oklahoma concluded that wildlife biologists and range managers can develop plans that “simultaneously consider biological diversity and agricultural productivity.”

Just as importantly, this viewpoint breaks down the idea that habitat conservation and rural economics aren’t compatible. With careful planning, the same acres can produce abundant wildlife, provide income for landowners and contribute in multiple ways to the local economy. Timber harvests can produce timberdoodles as grazing can produce grassland grouse.

Buy This Issue!