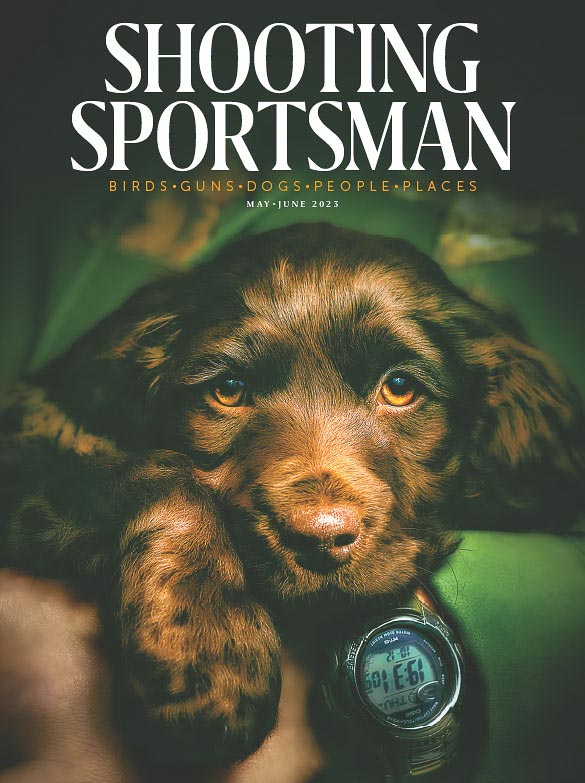

The do-it-all Boykin spaniel

Text by Tom Davis, Photos by Mark Atwater

Fifty years ago, few people outside of the state of South Carolina had heard of the Boykin spaniel much less laid eyes on one. For that matter, the Boykin wasn’t particularly well-known even within South Carolina, as the preponderance of dogs that went by that name were clustered around Camden, in the state’s Midlands region. That’s where the Boykin family, prominent landholders whose roots in the Palmetto State ran deep, had been breeding dogs of the same general “type”—compactly built brown spaniels with alertly intelligent expressions and coats that ranged from curly to wavy—since the early 1900s.

The Boykins and their sportsman-friends hunted turkeys in the dense woodlands along the Wateree River and ducks in the swamps and bayous of the river itself, and for those pursuits they needed an indefatigable natural retriever that loved the water, possessed a high-but-manageable prey drive and was small enough to fit comfortably in a “section boat”—a three-piece watercraft unique to that area that could be transported to the hunting grounds and assembled and disassembled on the spot. The first dogs to be called “Boykins” were whelped circa 1910, and therein lies a charmingly unlikely story.

One Sunday a year or two before that blessed event, a man named Alec White, who lived in Spartanburg, South Carolina, was walking home from church when he noticed that a nondescript brown puppy was following him. White took the little male home . . . and there he stayed. Christened “Dumpy” in reference to his diminutive stature, he proved to be a crackerjack little retriever—precisely the kind of dog White and his great friend Whit Boykin, who lived a few miles from Camden, had been trying to find for their duck and turkey hunting forays along the Wateree River.

Sent to Boykin for further seasoning, Dumpy so impressed him in every respect that, alone among the Boykin kennel, he was extended full house privileges. But it was his prowess afield that ultimately set him apart—and made him something of a local legend. According to one account “Boykin’s dog soon became known for his rare ability to find flocks of wild turkeys and scatter them, also to retrieve ducks, doves and quail under any and all conditions.”

At some point it occurred to Boykin that if he could locate the right female to breed to Dumpy, it might be a first step toward establishing a line of dogs with the characteristics of size, coat, performance and personality that could serve as a blueprint going forward. Boykin put out feelers (it was even in the church bulletin) and eventually got word that there was an unclaimed dog at the local railroad station that seemed to fit the description of what he was looking for. A female with a curly, reddish-brown coat, she appeared to be some kind of spaniel—close enough, anyway—so Boykin brought her home. He named her “Singo” and, after satisfying himself that her hunting instincts were adequate, introduced her to Dumpy.

And that’s how a couple of dogs whose futures looked anything but promising and by all rights should have been forgotten to history—mutts, to put it bluntly—became the Adam and Eve of the Boykin spaniel.

Of course, you can’t build an entire line of dogs on the genes of just two individuals—it’d be like trying to build a stool with two legs—and the people who took up the breeding of Boykin spaniels had no choice, really, but to introduce “outside” blood from time to time. While few if any records were kept in those days, it’s believed that the Chesapeake Bay retriever (smaller specimens of the breed, presumably), the springer spaniel and the cocker spaniel all contributed to the creation of the Boykin spaniel as we know it today.

Still, the breed that clearly influenced the Boykin’s development more than any other was the American water spaniel (AWS)—not coincidentally a breed that emerged from an environment

(the Wolf River marshlands of east-central Wisconsin) that is remarkably similar to the Wateree River country and, also not coincidentally, was designed to fill a similar multi-purpose role. Two prominent Boykin breeders of the 1940s and ’50s acknowledged “importing” AWS males to use as sires, and some, including retriever historian Richard Wolters, have speculated that Dumpy himself may have been an American water spaniel that was shipped from Wisconsin to South Carolina and somehow lost in transit.

In any event, while in general the AWS is a slightly larger and darker-eyed dog than the Boykin, a Boykin on the curly end of the coat spectrum is a virtual dead ringer for an American. There is, however, a foolproof way to tell at a glance which is which: Look at the tail. The Boykin’s tail, unlike the American water spaniel’s, is docked. The reason for this goes back to those formative years when one of the Boykin spaniel’s primary roles was to serve as a turkey dog—meaning to sniff out a flock of turkeys, flush them and then wait patiently with his master in a makeshift blind (remember, there was no camo clothing in those days) until the scattered birds regrouped at the flush site. As Wolters tells it in his book Duck Dogs, “Hunters could teach the dog to sit quietly and watch the birds coming back into gun range, but they couldn’t stop that excited tail from wagging. There wasn’t enough room in a blind for man, dog, and a swishing tail that rustled every twig and leaf within reach. Off came the tail.”

In Wisconsin, where there were no turkeys then, the tails stayed on.

All of which brings us to 1975. That’s when, on the strength of an article in South Carolina Wildlife magazine by a writer named Mike Creel, this formerly obscure breed—a breed whose provenance was sketchy and whose existence was unrecognized by any “official” organization—became an overnight sensation. Suddenly it seemed as if everyone in South Carolina had to have a Boykin spaniel and, with the demand far exceeding supply, they were willing to pay a pretty penny for the privilege.

Well, you can see where this is going. Because the breed was unrecognized and no “papers” came with the puppies, just about any smallish, brownish dog could be passed off by sharpies as a Boykin spaniel. There was no way to know; the buyer had to take the seller’s word that he was getting the genuine article.

The man who finally blew the whistle on this scam was a Camden veterinarian named Peter McKoy. He saw what was happening—some of his own clients were engaging in the persiflage—and he was also keenly aware of the tremendous pride the Boykin family took in the heritage of the spirited little dogs that carried their name.

McKoy expressed his concerns to members of the Boykin family and other reputable Boykin spaniel breeders, the gist of his message being that in order to ensure the breed’s integrity going forward two things were vitally necessary: a written breed standard and a formal registry. In 1977 the Boykin Spaniel Society (BSS) was founded for the express purpose of achieving these goals. The breed standard was adopted in January, 1979; then, between August 1, 1979, and August 1, 1980, 677 Boykin spaniels that met the standard (as determined by a screening committee) and whose ancestry could be traced back at least four generations were admitted as “foundation stock” for the Boykin Spaniel Registry.

From that point forward only dogs descended directly from foundation stock would be eligible for registration, meaning that you no longer had to take anyone’s word for the authenticity of the product. You could simply say, “Show me the papers.”

Implicit in everything the BSS does and stands for is its overarching zeal to preserve the Boykin spaniel’s superb field qualities and promote the breed as a versatile, highly capable hunting dog. The group’s single-minded devotion to this custodial ideal led it to decide very early on not to align itself with the AKC, the fear being that AKC recognition would take the breed to places—the show ring, for example—that the BSS believes it should never, ever go. As a result, the BSS is, as far as I know, the only independent sporting-breed registry in the US. In 2022 the BSS registered 761 litters that produced 5,099 pups.

For the record, the AKC formally recognized the Boykin spaniel in 2009, and as of this writing any Boykin with BSS registration is eligible for AKC registration as well. Some Boykin owners go this route in order to participate in AKC-sponsored hunt tests; most, however, don’t. The bottom line is that the BSS is the dominant player on the Boykin spaniel scene; the AKC is at best a minor presence.

Here’s a measure of the Society’s commitment: Through a nonprofit offshoot called the Boykin Spaniel Foundation, the BSS will actually reimburse you (up to specified maximums) for the costs of having your BSS-registered dog tested for as many as seven inheritable conditions, including hip dysplasia, exercise-induced collapse and collie-eye anomaly. How impressive is that?

Oh, and there’s this: In 1985 the Boykin spaniel was declared, by an act of the legislature, the official state dog of South Carolina—a year before its kissing cousin the American water spaniel earned that distinction in the state of Wisconsin.

These days, while you can find Boykin spaniels in every state of the Union, the breed’s stronghold remains the Old South: the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee, although there’s also a sizable contingent in Indiana. And while the majority of Boykins are still used primarily as retrievers, the dogs are no slouches in the uplands either—as a growing number of hunters will attest.

“They’re typically not as ‘busy’ as, say, a cocker or a springer,” said South Carolina sportsman Bill Crites, a longtime Boykin enthusiast and BSS official. “They’re a little more methodical. But I’ve shot literally hundreds of wild pheasants in North Dakota over my Boykins. They’re more of a ‘head-down’ dog, so they’re really good at tracking wounded birds.

“In fact,” he added, “I know multiple people who use their Boykins to track wounded deer. They all regret it, though, because once it becomes known that your dog can track deer, your phone never stops ringing!”

Rhett Owens, who hunts woodcock with his Boykins in the swamp edges and brushy cutovers of southeast Virginia, echoed Crites’s comments. “They’re great little woodcock dogs,” he said. “Maybe not as fast or as animated as a cocker or springer, but they’re definitely not plodders. And, of course, they’re terrific retrievers. They have wonderful dispositions too. For an all-around gundog that’s also a great companion, the Boykin’s hard to beat.”

“There’s not much holding ’em back,” said professional trainer Blaine Tarnecki, whose Hudson River Retrievers is located in northeast Georgia. “I know people who use their Boykins to hunt grouse, pheasants, quail, chukars—you name it. They’re truly one of the most versatile flushing-retrieving breeds out there, maybe the most versatile.”

Added Tarnecki, who’s probably “titled” more Boykins in hunt-test competitions than any other pro: “I get at least one call a week from someone who wants to know if a Boykin is ‘right’ for the kind of hunting he does. And I always say that unless he hunts waterfowl in big, cold water—Canada, the Pacific Northwest, someplace like that where a Lab or Chessie’s a better choice—he’s likely to be very happy with a Boykin.

“They’re great for hunting wood ducks in our Southeastern swamps and beaver ponds—that’s what they were bred for—but I’ve trained Boykins whose owners use them very successfully in green timber, ricefields, even on Chesapeake Bay. Retrieving geese is no problem for them; in fact, I just trained a Boykin for an outfitter in Texas who specializes in field hunts for light geese from layout blinds.”

Tarnecki’s experience also puts the lie to the stereotype that Boykins tend to be “soft” dogs whose training is something like walking a tightrope while juggling eggs. “I disagree with that 100 percent,” he said. “When I first started competing in hunt tests, most of the Boykins I saw were terrible. Well, what I finally figured out is that they were being trained like ‘frou-frou’ dogs, not hunting dogs. Every Boykin that comes to my kennel goes through the same training program that a field-trial Lab does. Obviously every dog learns at a different rate and has a different tolerance for pressure, but this idea that Boykins ‘can’t take it’ is nonsense. Some of my Boykins can take pressure better than some of my Labs.”

One stereotype that does hold water is that Boykins are unusually heat-tolerant—a quality that helps explain why they’re dove dogs par excellence. “Dove hunting is right in their wheelhouse,” said Bill Crites. “They’re just not bothered by the heat the way some other breeds are. I’ve never had a Boykin that ‘fell out’ or had to be put up because of getting too hot. Of course, I watch them carefully and make sure there’s water available to them at all times but, even so, the fact that they can handle the brutal heat during the early part of the dove season says something.”

The more you learn about the Boykin spaniel, the more obvious it becomes that Dumpy and Singo, whoever and whatever they were, made magic together.

Buy This Issue!

Read our Newsletter

Stay connected to the best of wingshooting & fine guns with additional free content, special offers and promotions.