The mind game of chukar hunting

The terrain lines on the map are stacked tight like growth rings on desert hardwood. Dawn casts the basin and range into stark relief. In this dry country the only water there is has been drawn out of the air and into a light frost on the grass. The first rays of sunlight have defrosted the south-facing slopes, but the ice will cling to the cheatgrass in the nooks and crannies for much of the day.

The rules are different in country this big. Consequently, you pick your hunting partners differently. A good chukar hunting partner will arrive at the right place at the right time. He is predictable. He reads the terrain and anticipates how it will move you across the landscape. He is generous and easy going and confident four-wheeling any old vehicle across a Bureau of Land Management two-track. Most important, you trust him as a person and an outdoorsman. Because if something goes wrong, your partner will be the one who comes looking for you. Also, when you roll into camp after a marathon day hunting, the last thing you want to do is deal with a jerk, narcissist or anyone who doesn’t laugh easily.

A bad hunting partner leaves you waiting at the truck long past when he said he would be there. A bad hunting partner pops up unexpectedly, shooting toward you or merely leaving a trail of prechewed ground for you and your dog to hunt over. A bad partner is a slow walker or a whiner who will complain about a lack of birds or cold weather or because you hurt his feelings.

The crew on this trip is spare, and the sense of humor dark. The members are game, willing to simply go at it and see what happens. We have a new addition this year—the youngest of the group, though an old soul. He has grit and makes a mean burrito. He’s not grizzled, but he’s fit and covers ground like an honest-to-god chukar hunter.

A couple of days before, Michael was hunting out of camp and overdue. We had heard a shot way out west 10 minutes before the end of shooting light. About 15 minutes after full dark Kyle, the new initiate, started getting worried. Tom and I agreed we would build a bonfire to make camp easier to find, “but let’s finish this beer first.” A couple of minutes later Michael rolled into camp, a shorthair at heel and a vest heavy with chukar.

I’d started the first morning of the trip low on sleep, overweight and needing to get my chukar legs under me. I took the young setter and started moving. Maggie made a great sweeping arc, at a dead run climbing a hill I had avoided. I followed her on a path of least resistance, climbing but at a gentle pace. And then she stopped. The Garmin said she was pointing, 425 yards away, straight uphill. I climbed like a mad man, panting, slipping on the ice-covered scree. I reached the summit, and she came right to me, happy as only a bird dog afield can be.

I looked around to see if I could find the birds flying and maybe mark them down. Instead I saw Tom, laughing at me. Giggling like a child who had just played the greatest joke of all time—having held the little setter by the collar, patiently petting her as I’d scrambled and raced uphill.

“I should shoot you,” I said as flat and cold as I could. But it came out more like, “I . . .” followed by gasping and retching. “I should . . .” more gasping and wheezing. “I . . . should . . . shoot . . . you.”

I had been pulled there involuntarily, but now I was in chukar country for real. To the east, a mountain range loomed another 2,500 feet up, and ahead of us was a dry creek and another hill. Down, then up again. Vertical lost, vertical gained. And if you want to kill chukar, you have to be casual about it. Birds climb up and fly down. Get used to it. When you find them, you chase them.

Tom managed to slow the giggling to a smirk. “Sorry, buddy,” he said. “I had to do it. You want to hunt together?”

We dropped into the creek bed and started upward again. The first day in chukar camp is always tough. Particularly after a year like this past. But you have to start climbing eventually—and truthfully, it’s not exactly the Himalayas. It’s more of a mind game than anything. You just have to steel yourself and go right at it. It helps to have a solid team to keep you motivated and moving.

Today we are three—a pair of dogs each, though we each hunt them one at a time. It takes a lot of dog power to cover this vast landscape. Keeping one in the bullpen helps over the course of a weeklong trip. The game plan is loose: Everyone picks a ridge and general direction, and we agree to be back at lunch or dark, though there is an unspoken expectation that you could be delayed by birds or back early if it’s clear you won’t find any. This is where careful selection of hunting partners really pays. I’ve hunted with people who always seem to end up in front of you. I know one guy in particular who could leave the truck going 90 degrees away and an hour later be shooting toward you. He no longer gets an invite.

The black basalt of the chukar hills is icy and slick. A few days earlier, as we’d planned for the trip and watched a snowy forecast, I’d called Tom in preparation. When I’d asked what he was up to, he’d said, “Reviewing the first-responder guidance on a broken femur.” I’d laughed, but later that thought would cycle through my head as I traversed the basin and range: climb, descend, climb, descend.

My companions are old friends. Guys who know your weak spots and have a knack for calling when you need to hear from them. We’ve hunted together enough to know where on the horizon to expect each other.

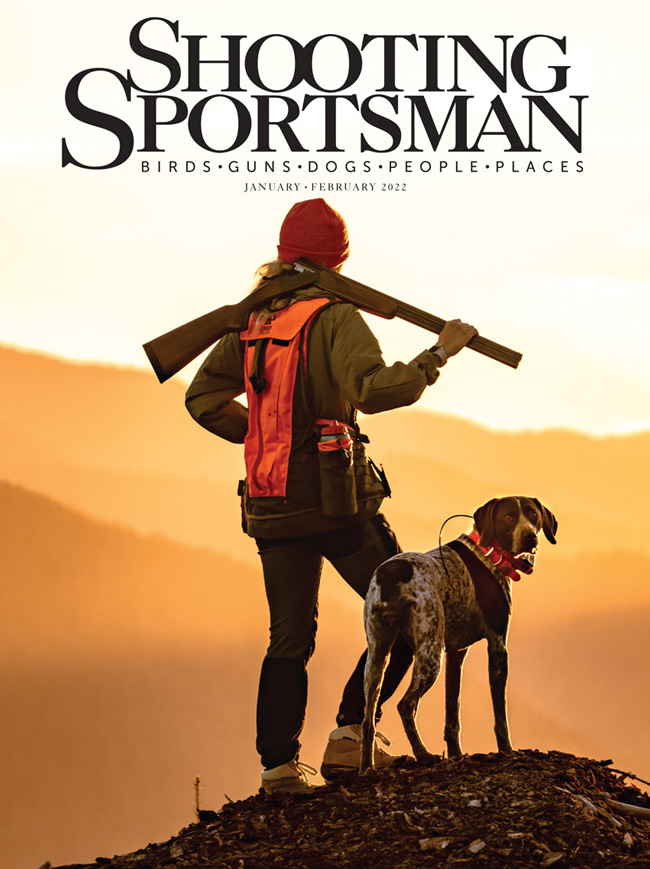

We choose three routes and head out, two setters and a German shorthair, all big runners, leading the way. A couple of hours later I see a figure on the next ridge, paralleling my path. He is a speck in the distance, but up here on the top of Nevada it’s reasonably flat. I can tell it’s Tom by the trademark hat and the setter’s gait out front. I angle toward him, suspecting that Michael must be in the canyon below. Within 15 minutes the three of us converge at the head of the canyon. It wasn’t part of the plan, but the terrain led us here. I pull my water from the pack and drink deep while I wait for them. Tom and Michael tackle the climb, and we traverse the flattop together, headed east to where I had pushed a covey of chukar earlier. Filled with the joy of pursuit and moving quickly, we recount our experiences so far. The dogs fall in line, eating up a vast swath of cheatgrass and sage while we debrief.

We begin making plans to split again when we see the dogs 150 yards ahead—all three pointing. We close the gap and see Michael’s excellent young shorthair, Trudy, and Tom’s setter, Mabel, the finest bird dog I’ve been around, backing my setter Luna. We are in range of the dogs, and I see the birds, nearly two dozen, running like hell. Luna breaks point. Up they go, and then we are shooting—too far, too behind, too bad.

“Bastards jumped wild,” Michael says. We all know it’s charity, but I’m too pissed at Luna to accept this gesture of kindness.

“Bullshit,” I yell, mostly to myself. “She blew those birds up.” Tom just laughs. I can’t tell if he’s laughing at me or the dogs or the birds. Or maybe he’s just laughing at the basic idea of hiking and scrambling a dozen miles over ice and scree following a dog, hoping she will prevent animals that are capable of flight from running so we can shoot at them with shotguns worth a year’s supply of meat.

It’s a big landscape and a harsh one. If you want to hunt here, it helps to be tough. Not just physically tough, but mentally. You have to accept the failings of poor shooting and less-than-perfect dogwork. You have to laugh at yourself, and it helps if you can take a practical joke. Our chukar camp is about friendship. It’s about laughs over beers and an unspoken policy that boils down to “don’t be a jerk.”

The dogs and the hunters are imperfect, but we are partners. We hunt hard, we laugh at ourselves, and when we are at our best, we manage to arrive at the right place at the right time.

Greg McReynolds works in wildlife conservation for Trout Unlimited. He writes for a variety of magazines and blogs at mouthfulloffeathers.com.

Buy This Issue!

Read our Newsletter

Stay connected to the best of wingshooting & fine guns with additional free content, special offers and promotions.

A well written article on Chukar Hiking. Thank You.

You still have more to learn about chukar hiking and chukar gun dog work but that will come with additional age and experience; however, the best part as you will find is just being in wildlands and among the wildlife with a gun dog!

Drew Wahlin, MBA, CPA

President Idaho Chukar Foundation & A 52 Year Professional Conservation Chukar Hiker (hike more shoot less and take lots of gun dog photos in the process)