The ins & outs of hunting diving ducks.

Story & photographs by Gary Kramer

As we left the protection of the harbor and headed into the darkness, guide Paul Gery gunned the outboard and a wall of salt spray came over the bow. It was so dark I could barely see the ghostly forms of my hunting partner, Greg Houser, and his Lab, Hank, sitting just ahead of me. Paul maneuvered the 25-foot boat past small islands and anchored ships. Twenty minutes later he backed off the throttle, and we pulled into the shoreline.

After unloading guns, shells, marsh stools, Hank and me, Paul and Greg pulled off the point and went about setting out six dozen canvasback and bluebill decoys. The dekes were set in long lines with large weights at each end to hold them in place against the current. With the decoys in place, Paul and Greg returned to the blind just as the sun peeked over the horizon. After getting situated, we had just pulled out the thermos to pour a cup of coffee when Paul pointed east and said, “Get ready!” I glanced up to see a knot of two dozen inbound ducks. They approached so fast that I barely had time to set down the thermos and grab my shotgun before Paul said, “Now!” I pulled the trigger of my Benelli Super Black Eagle twice and dropped one of the three scaup that ended up lying in the decoys. Hank was sent, and soon I was admiring a drake lesser scaup, or bluebill, as they often are called.

The rest of the morning was picture perfect for divers, with a stiff north breeze rippling the water, the tide being right and the birds decoying like they were being pulled in on a string.

Diver hunting often takes plenty of gear, preparation and effort, but the rewards of ducks (like these redheads) pitching into the decoys is worth it.

The experience of setting out huge decoy spreads, the speed of the ducks as they pitch into the blocks, the way the birds decoy in large flocks, and the preparation and effort required to take diving ducks have always made me appreciate diver hunting for the unique brand of shooting it provides.

Diving ducks, or divers, are so called because of their primary method of feeding, which is to dive below the surface of the water. That is not to say that divers cannot or do not feed on the surface, only that the majority of their food is obtained by diving. They have compact and streamlined bodies, and their feet are large and placed farther back than those of puddle ducks. Their musculature is different, as well, designed for diving rather than walking on land and slow versus rapid takeoffs. In North America diving ducks are comprised of canvasbacks, redheads, ring-necked ducks, greater scaup and lesser scaup.

Diving ducks can be hunted in a wide variety of habitats ranging from small marshes to large lakes and saltwater bays. Following are some of the areas divers are found and the tactics that will consistently put them in the bag.

LAKES & RESERVOIRS

Hunting big water for divers often means gunning on lakes and reservoirs. The classic image of a camouflaged boat surrounded by a spread of 100 decoys and a flock of hard-charging bluebills approaching is what typically comes to mind. While puddle-duck hunters certainly kill their share of birds on lakes and reservoirs, big water is the domain of diver hunters. Puddle ducks use these bodies of water primarily for sanctuary, but they often feed in other areas. In contrast, divers use big water for the full spectrum of their daily activities, including loafing and feeding, and they may never leave a particular lake or reservoir.

A boat is generally necessary to transport hunters and gear, set out decoys, retrieve birds and scout new spots. If you are setting up next to a bank or island and there is cover, pull the boat into or next to the cover. Setting up near points jutting into a lake is a good option, as birds pass by these areas and the field of view is greater. However, in many lakes and reservoirs shoreline cover is sparse, and it may be necessary to anchor a boat in open water to intercept birds traveling along local flyways. In such cases a boat blind and frame with natural vegetation and/or camouflage netting are required.

Successful big-water gunning can be accomplished by hunters without a boat. Many lakes and reservoirs have roads around their perimeters. Travel these roads, stopping at various vantage points, to search the lake with binoculars. Keep an eye out for points with adjacent sheltered areas, particularly during periods of bad weather and high winds. Diving ducks are tough customers and can ride the waves for hours, but when the wind really blows, they eventually seek more sheltered areas. No matter where you end up along the shoreline, concealment of some form (a portable blind, natural vegetation, rocks or driftwood) will be required.

RIVERS

While rivers are used extensively by diving ducks, they often are the areas least hunted. Virtually all rivers are considered navigable waterways, so once you are on the water, you can hunt almost anywhere. Be aware, however, of sections below dams and power plants, as often they are closed to hunting for safety purposes and may be designated waterfowl sanctuaries.

Conditions on rivers are more dynamic than on lakes, and ducks have a tendency to move around more. Water levels fluctuate, and you have to deal with currents and floating debris. From a safety standpoint, rivers can be dangerous, particularly during periods of high water. While these factors make river hunting a bit more complicated, hunting pressure is generally lighter than in many other areas.

Rivers can be accessed and hunted from either the shoreline or a boat. Boats can be used to scout, to transport hunters and gear, to access hunting areas and as shooting platforms. When scouting, look for divers in backwater sloughs, along the shoreline where tributaries enter, near emergent vegetation, behind islands, and late in the season below power plants and dams where there is open water. All of these areas hold ducks at one time or another, and a good decoy spread in the right location will provide action.

The boats used on rivers may or may not differ from those used on lakes and in coastal areas. I have hunted the Lower Columbia River for scaup from a boat that I use for salmon fishing: a 16-foot V-bottom aluminum skiff with a 50-hp prop-driven outboard. However, because of shallow sections or heavy debris loads, some rivers necessitate the use of flat-bottom boats and jet drives designed specifically for running rivers.

Once you have reached your hunting location, the boat needs to be camouflaged. Some hunters use blinds that attach to the boat and can be folded down and out of the way. Even if you have a boat blind, there are times that the boat will be used only to access an area, not as a shooting platform. Then it becomes necessary to get out of the boat and hunt from shore. Some of these locations might include a point or gravel bar where a driftwood blind can be used or a rocky shoreline where the best hiding place is among the rocks.

COASTAL ESTUARIES & BAYS

Coastal estuaries and bays are the undisputed domains of diving ducks. While some puddle ducks like black ducks and wigeon frequent salt water, divers along with sea ducks make up the vast majority of the tidewater duck harvest. Divers seek out coastal areas, particularly on their wintering grounds, for food and safety. These saltwater areas are important feeding areas, producing great quantities of shellfish and other invertebrates that the birds consume throughout the winter.

To hunt coastal areas it takes a boat and motor, knowledge of decoys and rigging, and knowledge of the tides. And, of course, safety must be considered at all times. Like duck hunters who frequent lakes and rivers, coastal duck hunters have to deal with changing weather patterns, bird movements and the other factors that play a role in a successful day afield. But unlike their freshwater comrades, coastal duck hunters must deal with tides. Tide books are available at most sporting goods stores and bait shops in coastal areas or can be found on the Internet at tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov.

Knowledge of the tides is vitally important for two reasons. First, at high tide there will be plenty of water to run your boat and reach shoreline hunting locations, but at low tide access within bays or estuaries becomes more limited. Second, without any other stimulus, diving ducks frequently move in response to changing tides. On bluebird days I’ve seen flock after flock of redheads pick up and head in one direction on the falling tide, and then reverse their flight direction on the rising tide. Likely the birds are moving to and from roosting locations to feeding areas where the water depths and currents are more favorable for foraging.

As with the other methods of diver hunting, you can use a boat or shoreline hiding place. Many of the best shoreline locations are on points of land that jut into bays, estuaries and coastlines. These points are productive, because they reach into the areas the birds are using and decoys are more visible to birds passing offshore.

Coastal areas are so large that reaching shoreline hunting locations, setting out decoys and retrieving birds generally requires a boat. The boat can be pulled up on shore, anchored in shoreline vegetation, pulled into a tide gut or anchored in open water and surrounded by decoys. The key to open-water boat hunting is using lots of decoys and placing the rig in a flight path or known feeding area.

THE DIVERS

In North America diving ducks are represented by five species: canvasbacks, redheads, ring-necked ducks, greater scaup and lesser scaup. Following is a short introduction to each.

CANVASBACKS

The canvasback is the largest of the diving ducks, with drakes identified by their chestnut-red head, long sloping bill and white “canvas” back and flanks. They are 20 to 22 inches long and weigh up to 3.5 pounds, with males averaging 2.7 pounds and females 2.5 pounds. While they breed in the Prairie Pothole Region and across Canada to Alaska, their main breeding areas are the parklands of western Canada. In winter they concentrate along both coasts, the Mississippi River Delta and the Upper Mississippi River. The canvasback harvest is greatest in the Mississippi Flyway (41%) followed almost equally by the Pacific (26%) and Central (25%) flyways. Canvasbacks are omnivores, consuming 80% plant material, particularly pondweeds and wild celery, and 20% animal matter, mostly clams and aquatic insects.

REDHEADS

The redhead is a medium-size duck, with males distinguished by their rufous head and neck and blue-gray bill with black tip and white band. They weigh from 2.1 to 2.6 pounds and are 19 to 20 inches long. Redheads breed from central Alaska to the Rocky Mountains, in the Prairie Pothole Region of the US and Canada, in the boreal forests, and in scattered locations in California, Nevada and the Great Lakes. Redheads commonly winter in coastal lagoons, with the majority of the population wintering in the Central Flyway—which not surprisingly shows the highest harvest. It is estimated that 80% of the redhead population winters in the Laguna Madre of Texas and Mexico. During the breeding season, redheads consume primarily aquatic insects along with some vegetation. Their main food in winter is shoal grass.

RING-NECKED DUCKS

Male ring-necked ducks are identified by their black head, breast and back, which contrast with their white sides, and their gray bill outlined in white with a black tip. They are 15 to 18 inches long and weigh from 1.4 to 1.7 pounds. Their principal breeding range is from the boreal forest of Alaska across Canada to the Maritime Provinces and south to the Great Lakes and New England. The largest winter concentrations are in freshwater wetlands along the Gulf Coast of Texas and Louisiana and in the Carolinas and Florida. About half of the annual harvest is in the Mississippi Flyway, with the Atlantic Flyway a distant second at 16% of the take. The tubers of hydrilla and the seeds of water lilies are favorite foods.

GREATER SCAUP

Called both bluebills and broadbills, greater scaup are similar in appearance to lesser scaup, though they are slightly larger and drakes generally have a green sheen to the head rather than purplish. Another difference is in their wings: Greaters have white wing bars that extend into the primary feathers, while the white wing bars of lessers do not extend into the primaries. Greater scaup are 17 to 21 inches long and weigh from 2 to 2.4 pounds. They breed farther north than the other divers, with the most important areas in Alaska and across northern Canada. They winter on both coasts and the Great Lakes, with 60% to 70% in the Atlantic Flyway and 20% in the Pacific. Greater scaup consume both plant and animal matter, including oysters, mussels, clams, wigeon grass and pondweeds.

LESSER SCAUP

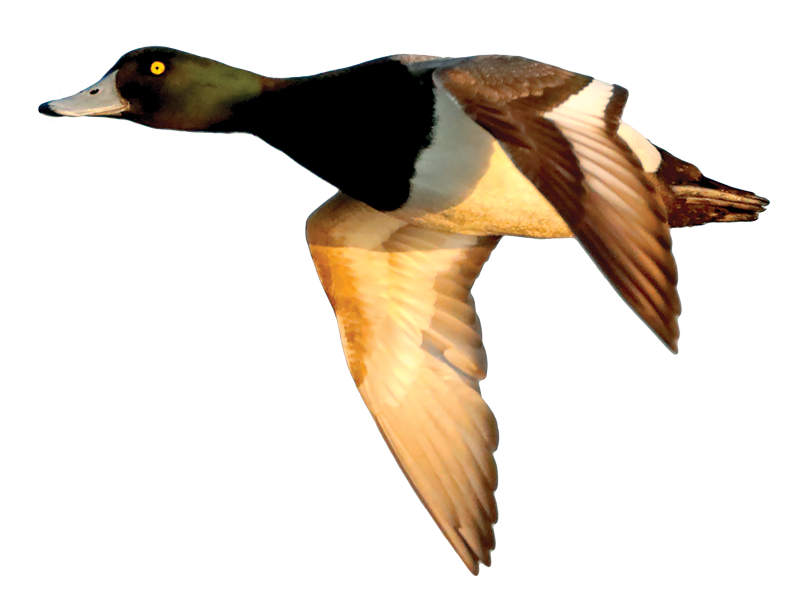

Lesser scaup, often referred to as bluebills, are the most common of the two scaup species in North America. The males have a black head with a purplish or sometimes greenish sheen, yellow eyes and a slate-blue bill. They are 15 to 20 inches long and weigh from 1.4 to 2.2 pounds. Their breeding area includes the boreal forests of Alaska and Canada and south into the parklands and Prairie Pothole Region. They winter along both coasts and the Gulf Coast in Louisiana and Florida, making migration stops along the way. The Mississippi Flyway leads in the harvest (45%), followed by the Atlantic (21%) and Central (20%) flyways. Lesser scaup consume mostly amphipods and pondweeds on their breeding grounds, whereas clams, zebra mussels and aquatic snails are important foods in winter. —G.K.

MARSHES

Compared to big-water areas, which generally require a boat and plenty of decoys and gear, marshes lend themselves to hunting alone or with a partner. Hunters typically access marshes on foot or in small boats and use small decoy spreads and a limited amount of gear.

I have seen areas where ring-necked ducks, which tend to feed in shallower water than other divers, are foraging alongside mallards and pintails. I also have seen marshes where mallards were preening and resting in deep water while yards away canvasbacks were diving and feeding. In these areas the addition of a dozen diver decoys to a mallard spread often will bring in divers, adding a new dimension to the bag.

Look for open-water areas within a marsh and locations where shallow water drops off into deeper pools. Also be on the lookout for submerged aquatic vegetation, which is a prime diver food and grows in water too deep for emergent vegetation like cattails and bulrushes. Divers feed on invertebrates, as well, so look for ducks surfacing from a dive with a freshwater clam or other food item.

LAYOUT & SCULL BOATS

Layout-boat hunting is one of the most interesting ways to hunt divers. Born during the heyday of market hunting, the layout boat quickly became popular with hunters targeting diving ducks. Because many of the areas frequented by divers are far from land or too deep for permanent blinds, the layout boat is considered by many to be the ultimate floating blind. Layout boats are designed to be “invisible” to ducks until the birds are over the decoys and in shotgun range.

Layouts are one- or two-man fiberglass, wide-hulled boats that have ultra-low profiles, are 12 to 14 feet long and customarily are painted dark gray. They are anchored fore and aft, with the bow pointing into the wind and the hunter facing downwind. Decoys are placed downwind, often with a string of trailing blocks to act as a guide for birds flying into the wind toward the boat.

Despite all the advantages of layout boats, their use requires more gear and equipment than most hunting methods. There is the boat and associated anchors, ropes and so on; a substantial decoy rig; and a “tender” to transport or tow the layout boat and carry hunters to the gunning area. Once hunters are transferred from the larger boat to the layouts, the tender is used to retrieve downed birds.

Scull boats are 14 to 18 feet long and produced in one- or two-man models. They are propelled through the water by a single curved oar that extends from a hole in the transom. The hunter lies in the boat and works the oar behind his head in a figure-eight motion. Most sculling is done downwind, so the wind is in the sculler’s favor. The best conditions for sculling are a light chop—just enough to keep any noises muffled and allow the boat to move through the water without a bow wave alerting the birds.

These boats generally are used without decoys, with the hunter spotting rafted birds and then sculling up on them. The hunter sits up to shoot when in range of the birds. Some hunters look for rafted birds from the shoreline before launching their scull boats. Others put their scull boats on larger craft or tow them until ducks are spotted.

During the past 30 years I’ve had the good fortune to hunt diving ducks throughout the US, Canada and Mexico. Yet still whenever I’m getting ready for a diver hunt, I experience some of the same excitement I felt on my first trip. I believe that a flock of redheads or scaup boosted by a 15-mph tailwind coming full tilt into the decoys is among the most awesome sights in all of waterfowling.

Read our Newsletter

Stay connected to the best of wingshooting & fine guns with additional free content, special offers and promotions.