By E. Donnall Thomas Jr.

Photograph by Lori Thomas

January 17, 2001, was a day of infamy, according to local lore around my rural Montana home. That’s when President Bill Clinton signed an executive order creating the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument from 377,000 acres of land already managed by the federal government. Dire predictions began flowing faster than the river itself. Farmers would lose access to their land. Grazing leases would not be renewed, and family ranches would go under. It was nothing but a land grab by the federal government. Motor vehicles would be banned and so would hunting. Fortunately for all parties threatened by this doomsday scenario, 18 years have come and gone and none of this has happened. Resentment still seethes throughout the area, however, and I still keep hunting “The Breaks” just as I always have.

National monuments often make the news these days, largely because of the Trump administration’s decision to reduce the size of two large monuments in Utah: Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante. Serious talk of doing away with national monuments altogether surfaces regularly. The discussion is both complex and politically charged. Here I’ll focus on the issue as simply as possible from the hunter’s perspective.

Misconceptions persist throughout the hunting community regarding opportunities on national monuments. Because of uncertainty and outright disinformation, many sportsmen are missing good public hunting on some of the country’s best habitat, particularly in the West.

Presidential authority to create national monuments dates back to the 1906 Antiquities Act, shepherded through Congress by Rep. John Lacey (R-IA)—famous today for his early work combatting illegal trade in wildlife—and signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt, whose credentials as a hunter-conservationist should be known to us all. Since then 16 presidents (eight from each major party) have used this authority. Today there are 130 national monuments around the country (although this number is subject to change). Some are intrinsically of little interest to hunters, including the smallest (320-square-foot Father Millet Cross, in New York) and the largest (140,000-square-mile Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument, near Hawaii). Many monuments contain excellent habitat for big game, and some are home to waterfowl and upland birds. The vast majority of national-monument acreage is open to public hunting, as dictated by state regulations.

Most national monuments are administered by the National Park Service (NPS), the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) or the United States Forest Service (USFS), with a few overseen by other agencies. While the number of monuments managed by the NPS (approximately 90) is higher than all others combined, many of these are small and contain little or no significant wildlife habitat. By far the greatest acreage included in national monuments as well as the best hunting opportunities are overseen by the hunter-friendly BLM.

In general federal lands managed by the NPS do not allow hunting because of language in the 1916 Organic Act, which created the Park Service in the first place. However, there are some exceptions, most of which are found in Alaska because of special terms established in the 1980 Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act. Conversely, most national monuments in which hunting is prohibited are managed by the NPS, while hunting is allowed in almost all managed by the BLM and USFS.

An example from California is a case in point. In 2016 some 20,000 acres of the Mojave Natural Preserve, managed by the BLM, became the Castle Mountains National Monument, managed by the NPS. This land holds good populations of several important big-game species as well as quail, all of which could be hunted according to state regulations prior to the monument designation. For administrative (as opposed to biological) reasons, the land managed by the NPS is now closed to hunting. Similar confusion exists at other monuments in which administrative authority is divided between the BLM and NPS, such as Craters of the Moon, in Idaho, and Parashant, in Arizona. However, these examples are exceptions rather than the rule.

So it’s complicated, but not nearly as complicated as many hunters assume. The vast majority of national-monument land is open to legal hunting according to state law, and these public lands are easy to identify. Is the hunting experience worth the effort? Granted, there aren’t a lot of gamebirds in the one-acre Castle Clinton National Monument, in New York City, or in many of the other small Eastern monuments managed by the NPS.

Head to the West, however, and it’s a different story. There national monuments offer millions of acres of public hunting managed by the BLM and USFS, with regulations determined by state agencies. Big game often provides the main attraction, but many offer excellent upland hunting, especially for species such as chukars and quail.

Navigating federal websites for specific information about hunting can be frustrating. To the best of my knowledge, there is no master list of monuments that allow hunting. Wikipedia has a comprehensive list of monuments (search “national monuments”) that includes size and management agency but not specific information on hunting. Contact individual monuments listed there or visit blm.gov, fs.fed.us or fws.gov/

hunting and search “hunting.” Confirm by contacting monument headquarters and reviewing individual states’ regulations, which usually have more accessible information about hunting in monuments within their borders.

From the hunter’s perspective, national monuments can be done right, or they can be done wrong. At worst they can represent unnecessary regulation and needless loss of hunting opportunities. At their more frequent best, monuments provide important habitat safeguards and excellent public hunting opportunities. Sportsmen and the organizations that represent us need to look beyond the heated and frequently inaccurate political rhetoric that dominates the discussion today and become involved, provide input at the local level and work to ensure that national monuments meet legitimate public needs consistent with their mission. The rewards can be substantial.

Monumental Examples

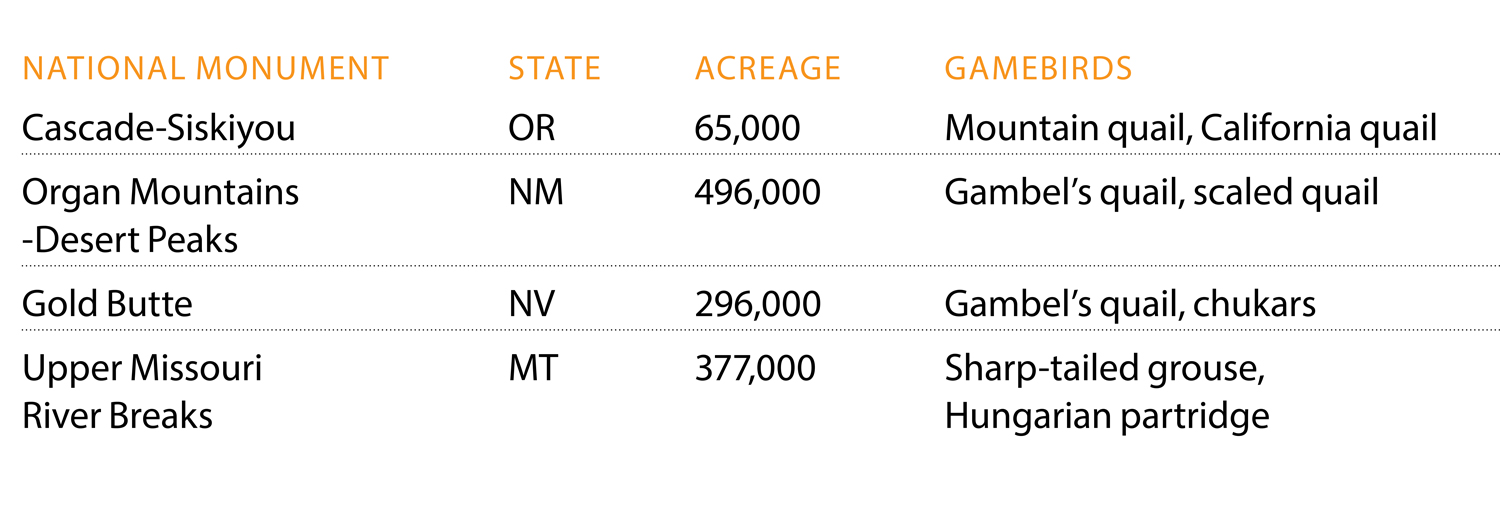

Here are just a few national monuments that offer wingshooting opportunities. Depending on seasonal conditions, most offer some hunting for waterfowl and doves as well. Notice that it doesn’t take long to add up to a million acres of opportunity.

Read our Newsletter

Stay connected to the best of wingshooting & fine guns with additional free content, special offers and promotions.