Cuba’s Finca Vigía gives up its secrets

By Silvio Calabi, Steve Helsley & Roger Sanger

As the research for the second edition of Hemingway’s Guns was underway, Roger Sanger attended the 2014 Hemingway Festival in Ketchum, the resort town in Idaho that Ernest Hemingway frequented and where he lies buried. The Festival has taken place every September since 2005, but 2014 was the first time that Ada Rosa Alfonso Rosales attended. Ada Alfonso is the director of Cuba’s most popular national attraction: the Museo Ernest Hemingway Finca Vigía—the man’s home for 21 years. Sanger fought his way through the crowd, presented Ada with a copy of the first edition of the book and then, through her interpreter, asked the million-dollar question: By chance are there any guns still at the house?

“Sí, sí, ciertamente,” came the reply: Yes, certainly. We have several of Hemingway’s guns. And then: “Te gustaría verlos?” Would you like to see them?

Would we . . . ? Yes. Yes, we would like to see them. And just like that we were invited to Cuba to curate the guns left in the Finca Vigía, “Lookout Manor,” when Ernest and Mary abandoned it, 19 months after Fidel Castro finally toppled the dictator Fulgencio Batista, on January 1, 1959. Egyptologists invited into King Tut’s tomb couldn’t have been more excited.

There’s an old saying that ‘guns have only two enemies: rust and politicians.’

In early February 2015 we gathered in Miami, where Mike Wysocki, a Hemingway aficionado and contributor to our book, joined us for the flight to José Martí International Airport. On our arrival, among the throng of people awaiting relatives from the US, we found our driver and guide/translator and a spotless Mercedes-Benz Sprinter van. The highway into Havana was remarkably traffic-free and dotted with billboards still proclaiming La Revolución, with heroic pictures of the Castro brothers, Che Guevara and late Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez. Havana has a modern diplomatic quarter that resembles a Miami neighborhood, complete with BMWs and Mercedes-Benzes, but the rest of the city truly is populated with relic Fords, Chevrolets, DeSotos, Buicks and the like. (The sale of American automobiles—and their parts—ended with the embargo imposed by JFK’s government on October 19, 1960.) Today many of these vintage cars serve as taxicabs, most spew clouds of smoke and it’s anyone’s guess what’s now under their hoods.

Before Hemingway moved into the Finca Vigía, in May 1939, he occupied Room 511 of the Ambos Mundos Hotel, in the heart of Old Havana. Our hosts arranged for us to have the adjoining rooms. There was no internet access, a shock to modern norteamericanos, but the rooftop bar and the view toward the harbor, not to say the friendly staff and palpable Hemingway aura, were fine compensation.

Arriving at the Finca’s 15-acre compound behind busloads of tourists from Europe and Asia (and the occasional horse-drawn cart), we were greeted warmly by Ada Alfonso and her staff. We spent two full days there, using as our studio the room on the ground floor of the house’s tower that Ernest and Mary Hemingway had given over to their dozens of cats. (It had been cleaned.) We were given extraordinary access to the Hemingways’ personal possessions and documents, including seven guns—two rifles and five shotguns—that now appear in our book:

Adamy 12-gauge No. 29392

L.C. Smith .410 No. FWE103621

Liège 28-gauge No. 191024

Mannlicher-Schoenauer 6.5mm Model 1903 No. 22108

Springfield Model 1873 No. 13591—converted to a harpoon gun

Winchester Model 21 20-gauge No. 14866

Winchester Model 42 .410 No. 8781

▲ The Club de Cazadores del Cerro, Cuba, 1950–’51. Hemingway with three of his favorites: Adriana Ivancich, his 21-year-old Italian flame; the Beretta S3, which she is holding; and the W. & C. Scott gun. Papa made a fool of himself over Adriana, who (with her mother) was a house guest at the Finca Vigía from October 1950 into February ’51. The Beretta, No. 5991, is a 12-gauge over/under that Hemingway acquired in Venice in the late 1940s. In 1963, two years after Papa’s death, Abercrombie & Fitch sold the gun on Mary Hemingway’s behalf for $250. Today it is on display in the Beretta Gallery in Manhattan. The Scott, No. 102793, was a Monte Carlo B pigeon gun made c. 1923. Papa bought it, too, in northern Italy in the late ’40s, and it went on safari in East Africa in 1953. Many years later, one of the bird boys at the Club de Cazadores claimed that in the early ’50s he sometimes loaned the Scott, without Papa’s knowledge, to a young lawyer named Fidel Castro for shooting practice. The Scott is the gun the authors believe Papa used to end his life, in 1961; Mary ordered it destroyed, and the pieces were buried in an Idaho field where later Adam West, TV’s Batman, built a home.

▲ On October 16, 1942, Hemingway paid Abercrombie & Fitch $275 for a secondhand 12-gauge boxlock ejector over/under, Serial No. 29392, made by Gebrüder (“Brothers”) Adamy, in Suhl, Germany. The action was inscribed “For Wm. F. Beal,” and it had been consigned to A&F by a Mrs. W.F. Beal. The Adamy name is little known even in Europe, but $275 for a used gun in 1942 suggests that it was of some quality. Today the gun is much the worse for time and inattention. Adamy’s records did not survive WWII, but Helmut Adamy, who manages the company now, believes that the Beal/Hemingway gun dates to the 1920s, when his grandfather Albert and granduncle Franz founded Gebr. Adamy.

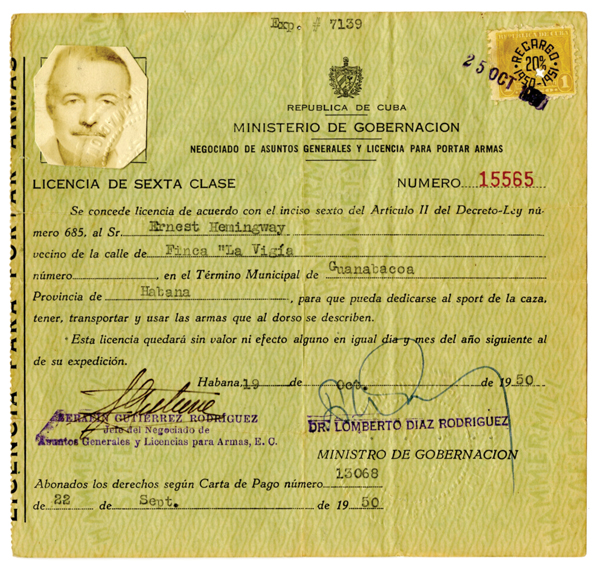

▲ “This license is granted in accordance with paragraph six of Article II of Legislative Decree no. 685, to Mr. Ernest Hemingway, a resident of the Finca Vigía in the municipality of Guanabacoa, Province of Havana, so he may engage in the sport of hunting, [and] have, carry and use the arms that are described overleaf. This license shall be null and void on the same day and month of the year following that of issue.” Dated September 22, 1950. This and many other documents, including lists of permitted guns, are archived at the Hemingway house outside Havana.

▲ The tower side of the Finca Vigía, an Italianate villa built in 1886 and bought by Hemingway in 1940 for $12,500. With private help from the US, Cuba has been able to refurbish and stabilize the house, but in a tropical climate this is an ongoing campaign. The Finca contains Hemingway’s library of 9,000 books as well as thousands of letters, manuscripts and photographs and most of Ernest’s and Mary’s furnishings and belongings, left behind when they departed on July 25, 1960, for their new home in Idaho.

▲ L.C. Smith .410 No. FWE103621. Hemingway may have bought the gun new, as it was shipped in July 1928 to Von Lengerke & Antoine, the Chicago sporting-goods store, and he mentioned a .410 in a letter the same month. Factory records list this as a Field Grade with 26-inch barrels, and “FWE” stands for Featherweight Ejector. Its $57.25 retail price included $17.25 for the ejector upgrade. In the early 1940s both of the younger Hemingway sons, Patrick (born 1928) and Gregory (“Gigi,” born 1931), won trophies with this gun at Cuba’s Club de Cazadores del Cerro, the shooting club where Papa was a member. According to family lore, Gigi at the age of 10 beat 24 men in a pigeon match with this gun—a remarkable feat.

▲ Winchester Model 21 No. 14866—a Standard-grade 20-gauge with 26-inch barrels that was ordered on October 2, 1940, by the Strevell-Patterson Hardware Co., of Boise, Idaho, for W.P. Rogers, general manager of the Sun Valley Co., and “Ernest Hemmingway [sic].” Rogers was the Sun Valley Resort’s general manager at the time, remembered as “fiery but warm, demanding but appreciative, wholly hands-on always, a greeter of every incoming bus.” Evidently his hospitality extended to ordering a gun for one of his celebrity guests. Ernest’s girlfriend, Martha Gellhorn, shot a loaner Model 21 better than she had the Model 42, so Ernest bought three 20-gauge M21s, separately, in the fall of 1940. Why three, at about $120 apiece? Possibly because he could—For Whom The Bell Tolls came out in October to rave reviews, and then Paramount Pictures paid a record $150,000 for the movie rights to it. As well, Martha’s 32nd birthday was November 8, and she and Ernest married on November 21; Papa was in love.

▲ Winchester Model 42 No. 8781—probably made in 1933, the first year of production. Along with the low number it has the pre-war rounded forend with 18, not 16, grooves. Into the bottom of the grip are carved the letters “MG.” In 1939, when she was using this gun, Martha Gellhorn was not yet Mrs. Hemingway III, hence MG and not MGH (as on one of the Model 21 Winchesters a year later). This .410 reportedly had mechanical problems—and the bottom of the action shows signs of bodgering (amateur gunsmithing).

▲ Another shotgun still at the Finca Vigía is this 28-gauge boxlock, Serial No. 191024. The right barrel is marked “Faustino Lopez” (likely the retailer) and the left “Habana.” The rib reads: “Manufacture Liègeoise D’Arms a Feu, Liège, Fondee 1866, Grand Prix Paris 1900” (Made by Liège Firearms, founded 1866, winner of a Grand Prize at the Paris Exposition of 1900). In front of the barrel extension is a crown with “ML” below; then “Acier Special” (special steel), then another crown with “XL” below. It has 26-inch barrels and a Greener-style safety and crossbolt; there are holes in the stock and the under-rib for sling eyes. According to a note in Hemingway’s handwriting on a list of guns, it belonged to Thorwald Sánchez, one of his Cuban friends, who owned an ice cream factory.

▲ For his 50th birthday (July 21, 1949) Hemingway ordered an odd assortment of items by mail: signal flags, cases of Mexican food, a US Navy ship’s clock, a waterproof flashlight and more. But his favorite gift to himself was this pair of Winchester 10-gauge blackpowder signal cannons, posed here on the garden wall at the north side of the Finca, looking toward Havana.

We also found the pair of 10-gauge blackpowder signaling cannons that Hemingway loved to salute arriving guests with and that always sent the household dogs and cats into hysterics.

There’s an old saying that “guns have only two enemies: rust and politicians.” These seven had been ravaged by both and were in poor condition. Cuba instituted gun registration well before the Castro revolution (there have been a half-dozen uprisings since the island declared its independence from Spain, in 1868), so it was easy for those in power to seize private firearms—but Fidel Castro, a great admirer of Papa Hemingway, set aside the Finca as a museum and protected its contents. Still, the Hemingway guns had been crudely deactivated, and the tropical climate had taken its toll as well. Sad as it was to see the damage, we were thrilled. Our long quest had brought us to Hemingway’s home and put seven more of his guns—“lost” since 1960—directly into our hands.

Several were completely unexpected. Some we’d seen in Hemingway photographs. The Adamy over/under we knew from the records of Abercrombie & Fitch, where Hemingway bought it in 1942. The Model 21 we traced to a hardware store in Boise, Idaho, in 1940, and from there to the Sun Valley Resort. Two of these guns had been grabbed briefly by the Cuban army in 1947 during rumors of unrest. From documents in the house we learned of more guns yet, or learned new details about these guns and guns already in our records. It is significant that we did not discover Hemingway’s English shotgun, the fateful W. & C. Scott & Son pigeon gun, but we finally found its serial number: 102793. (Fateful because we believe it was the Scott that Papa used to end his life—before breakfast on July 2, 1961, in Ketchum—and that his widow, Mary, handed to a local welder to destroy, lest it become a curiosity; significant because finding the Scott intact would of course have deep-sixed our theory. The “CSI”-style investigation that led us to the Scott is detailed in the book.)

We were able to linger in each room of the house, which is closed to the public, and examine such things as Papa’s trophies and safari gear and even a copy of The Old Man and the Sea in Russian Cyrillic—in Braille. Our iPhones captured 60 scratchy seconds of “Aida,” played for us on Ernest’s and Mary’s gramophone. As the music floated through the house, visitors gathered to peer in the windows and aim cameras at us—and we overheard speculation that Helsley, with his beard and physique, must be a Hemingway relation!

Our iPhones captured 60 scratchy seconds of “Aida,” played for us on Ernest’s and Mary’s gramophone.

Hemingway’s friend and biographer, A.E. Hotchner, wrote that on his first visit to the Finca Vigía, Hemingway showed him “a yellowed four-by-five picture of Ernest, aged five or six, holding a small rifle. Written on the back in his mother’s hand was the notation, ‘Ernest was taught to shoot by Pa when 21/2 and when 4 could handle a pistol.’” His grandfather Anson Hemingway gave him a single-shot 20-gauge shotgun on his 12th birthday. Ernest invented a high-school gun club and went to his first war when he was 18. He was the son and grandson of hunters and anglers who taught him not only technique but also the ethos of the sportsman: to learn about and respect the game.

Hemingway hunted in Michigan, Arkansas, Maine, New York, Florida, Idaho, the Dakotas, Montana and Wyoming as well as in France, Italy, Greece, Spain, Cuba, Kenya, Tanganyika (Tanzania) and probably elsewhere. He shot pigeons in competition in the US and in Cuba and Europe. He went on two long safaris in East Africa, in 1933 and 1953, where he was guided by one of the white hunters who had accompanied Theodore Roosevelt on his 1910 expedition. (“White hunter” was a perfectly acceptable term in his day.)

For all of his passion as a hunter and shooter, not to say his considerable income, Hemingway spent his money on function, not extra engraving or fancy wood. He also valued the familiarity he’d built up with certain guns over time. Favorites, though well cared for, became battered and bruised and bare of finish from decades of use. Like the car one drives or the mate one marries, guns are an expression of wealth, status, education, experience, skill and personal style. Hemingway’s guns, as well as how he acquired them and what he did with them, tell us about him as a man, and they helped to shape his legendary masculinity.

As well, every one of us has examined a well-worn gun of some sort and thought: Who used this thing? Where has it been? What great adventures has it been part of? Talk to me! To some extent, we’ve been able to make Papa’s guns talk.

A version of this article appears in the second edition of Hemingway’s Guns (Lyons Press, 2016). This edition is 100 pages longer than the first book (2010), with many more photos, and presents the results of a further five years of research as well as the expedition to Cuba.

Subscribe to Shooting Sportsman at this special price (6 issues for $26)