Hunting desert quail on the Turner Family’s Armendaris Ranch

The Chihuahuan Desert possesses a seductive beauty that belies its harshness. The expanse looks majestic and inert from the edge of a road or through the eyepiece of a lens. But even a simple excursion into its vastness requires extra care, and anyone failing to see it as more than just a pretty place courts disaster. The flora growing from its thirsty soil will wound bare flesh, and the loose and jagged rocks guarding its mountain slopes imperil an approach from anyone other than the surefooted and well-shod. Sudden storms and extreme temperatures compound the danger, and any species, including humans, surviving in this desolate splendor must negotiate with the habitat on its terms. The Chihuahuan Desert cannot be tamed. But the delicate balance of its ecosystem can be easily disturbed and destroyed, and the pollution of such pristine places ultimately sows the seeds of our own demise.

Champions of conservation understand the urgency of mitigating the damage, and among those with both the will and the means to impede the advance of ecological disaster, renowned entrepreneur and philanthropist Ted Turner stands tall. His current roster of intensely managed holdings makes him the second-largest private landowner in the US—and thanks to my friendship with his son Rhett, I received an invitation to hunt desert quail for several days at his Armendaris Ranch, in New Mexico.

In mid-January we landed in Albuquerque around midnight under a full moon and drove bleary-eyed through the desert down I-25, arriving at the Armendaris near the witching hour. We each claimed a well-apportioned room for a few hours’ sleep before waking with the sun to enjoy a hearty breakfast prepared by Chef Giovanni Lanzante and his wife, Kelly. Two plates topped with scrambled eggs, bacon and skillet fried potatoes flanked a centerpiece of assorted pastries and a bowl of mixed berries. After savoring every bite, I gathered my vest and chaps and walked outside to marvel for a moment at the morning sky. Though I had read enough Cormac McCarthy to imagine a desert landscape, my eyes had never beheld its grandeur. A bank of low clouds floated over an eastern chain of the Fra Cristóbal Range and veiled the sunlight, igniting the heavens in a fiery blaze above a plain of gramma grass.

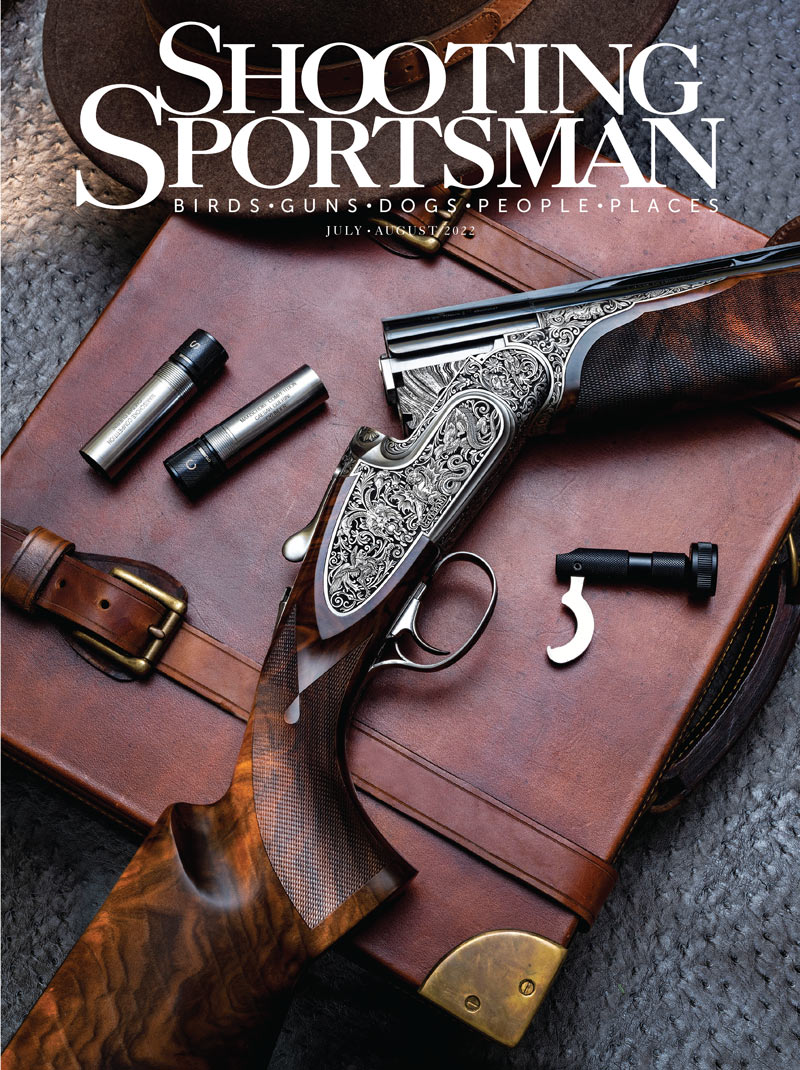

Rhett introduced me to our guides, Mike Mader, Chris Thayer and Brian O’Dell, who had finished loading the trucks and were ready to head out. They led us down dirt roads carved through the more than 360,000 acres of unsullied wilderness while Rhett and I followed a comfortable distance behind. Outbuildings and other objects indicative of civilization receded in the rearview as we probed deeper into the desert. A thick grove of dogwood and mesquite trees appeared in the distance rising above a sea of tumbleweed, yucca and prickly pear. Mike pulled his truck into a turnaround, and when we parked beside him and opened our doors, mourning doves swarmed from the wooded oasis like bees from a hive. Mike and Chris put a pair of pointers and a Labrador retriever on the ground while Rhett and I loaded our over/unders and stuffed cartridges into our vests. Then we followed the dogs into the cover.

A stand of desert willows grew along the banks of a bone-dry creek bed, and a cool winter wind whispered through their bare branches. We walked cautiously atop piles of fallen deadwood that had been deposited during a summer monsoon. “Though we’re still in a drought across much of the area,” Chris explained, “we got a lot of rain here at the Armendaris.” It turns out that “a lot” of rain in this area is barely 10 inches a year, and I marveled at how anything, much less a delicate quail, could not only survive but thrive in this habitat.

It wasn’t long before the dogs found scent and locked on point, and as they did, Mike spotted movement on the desert floor. “We got some scalies on the run here,” he cautioned. When the dogs broke off, Rhett raised his gun to the ready. As we approached where the dogs had been pointing, a single scaled quail bolted from the cover, presenting an out-and-away shot. Rhett tumbled it before I could shoulder my gun. Mike noticed my unpreparedness and said politely in a low voice, “These desert quail didn’t read the same playbook as bobwhites. The coveys usually run on you before rising, and then we hunt the birds that stay behind.” Chris collected the first quail of the day from Mike’s yellow Lab, and we walked deeper into the cover.

Another covey flushed wild, leaving several singles behind, and we moved toward the dogs holding point about a hundred yards ahead. Having gained a little knowledge from the first covey, I brought my gun to the ready position. A pair of scalies flushed between Rhett and me and flew out and away, and I cleanly missed with both barrels while Rhett brought one down. “I’m glad you’re here,” I said, “or we’d both starve. I need to get with the program.”

Chris added another bird to his gamebag, and we circled back toward the trucks. When we neared the vehicles, I spied Brian standing atop the dog box in the truck bed with a pair of binoculars glassing the horizon for running coveys. He hopped down to greet us, and I felt obliged to explain why I had more empty cartridges to show than quail. “Yep,” he said smiling, “These scalies wear track shoes compared to bobs. They also call them ‘cotton tops’ because of the little white mohawk on their heads.”

‘We grew up learning how to respect the resource and to enjoy what it gives us.’

While we watered the dogs, Rhett, Mike and Chris offered additional guidance about how to hunt these birds; then we boxed the dogs and mounted up to find more quail.

Long stretches of windshield time offered an opportunity to discuss the importance of conservation and the Turner family’s prodigious role in saving wild spaces. I asked Rhett, for example, about the herds of bison and East African oryx that we were seeing loitering on the plains. “My father acquired this ranch in 1994 because of the unique biosphere offered by the tract,” he said. “He stabilized the habitat for desert quail, and while the oryx were already here, he introduced bison and desert bighorn sheep. The desert bighorn almost went extinct 25 years ago; now there are huntable populations in New Mexico.”

During his domestic and international travels, Ted Turner saw the damage being done to the environment and felt the need to give back in a bigger way. In the late 1970s he started buying large pieces of property, and he continued acquiring them throughout the ’80s. He set a goal of having 1 million acres under intense conservation management by the mid-’90s, and after meeting that he aimed to preserve another million acres into the 21st Century. In 1990 he launched the Turner Foundation to support environmental causes across the globe, and since then the foundation has awarded more than $400 million in grants to address problems facing the planet.

“My father’s purpose with the foundation wasn’t to simply give money to environmentalists,” Rhett said, “but to consider how these efforts could become sustained solutions.” To ensure its future, his father involved his children and grandchildren in the foundation, and today Rhett serves as a director alongside his four siblings.

In tandem with his work for the foundation, Rhett created Red Sky Productions in 1999 and released his first documentary film, Pollinators in Peril, an environmental documentary that led to a career of producing and collaborating on several similar projects. His latest efforts take the form of a coffee-table book of rich photography titled Conserving America’s Wildlands: The Vision of Ted Turner. Its release this fall will be the culmination of several years spent traveling between the domestic Turner properties and capturing images of their wildlife and habitat. According to Rhett: “I felt no one had documented the conservation work that’s been achieved by my father, so I set out to do this a few years ago. We’re enthusiastic about this opportunity to showcase the properties and talk about how his passion for the environment has benefited the greater good.” Many of Ted Turner’s current holdings are open to the public or have been donated to state governments for use as parks and ecological research tracts, such as Hunting Island State Park, in South Carolina, and the McGinley Ranch, in Nebraska.

Alongside a legacy of environmental philanthropy, the Turner family’s appreciation for sporting life precedes it. “We grew up learning how to respect the resource and to enjoy what it gives us,” Rhett said, “and I love hunting and angling as much now as I did then.” Several of the Turner properties offer commercial hunting opportunities, and while quail hunting at the Armendaris is restricted, the ranch does accommodate clients for big-game hunts.

Mike led us toward a section of the Fra Cristóbal Range closer to the ranch where we would hunt the rest of the day. Lush grasses replaced the thorny shrubs encountered on other parts of the property, and thin groves of juniper trees scaled up the hillsides instead of creosote and cacti. We parked and followed the dogs up a steep grade toward a small mountain crest, and with the elevation running to about 6,000 feet, my breath shortened along with my stride. Without warning, a covey of Gambel’s quail sailed from the cover. We watched them settle farther up the mountain and pressed them until our legs and lungs burned. When one of the remaining singles flushed, my gun came to shoulder and my first shot toppled it into a valley.

“Nice shot,” Chris said from behind.

“It only counts if we find it,” I replied.

We tiptoed down the slope behind the Labrador, which winded the bird not far from our mark and delivered it to Chris.

Rhett collected a couple more quail from the covey before we descended the mountain.

When we returned to the lodge, the guides brought the birds to Chef Lanzante, who prepared them while we cleaned up for dinner. We reconvened in the dining room and grazed on a hearty charcuterie board before Kelly emerged from the kitchen with two plated entrées featuring the quail we’d taken that day. With some simple Greek seasonings, Chef Lanzante had allowed the flavor profiles of the birds to speak for themselves. The meal concluded with a decadent dessert of chocolate pound cake.

After dinner Rhett and I conversed around the firepit and toasted the day’s hunt. The warm whiskey insulated us as the mercury plunged, and a bright full moon held court among the stars. I gazed up at the night sky and wondered if there were any places like Earth among those heavenly bodies. Science says that, given the number of stars in the universe, the probability of finding another Earth-like planet is not only possible but likely. But getting there would require technology far beyond anything we currently have. If humans hope to survive long enough to reach the stars, we first must care for this planet—the only known habitable space we have. The Turner family understands this and, through its legacy of conservation, is offering aid for our planet today that gives us a chance for a tomorrow.

Oliver Hartner is a South Carolina-based writer covering sporting-life interests. His work has appeared in Covey Rise, Quail Forever Journal, USA Today Hunt & Fish and South Carolina Wildlife. He serves on the South Carolina State Committee of Ducks Unlimited as its secretary.