Pursuing the elusive mountain quail

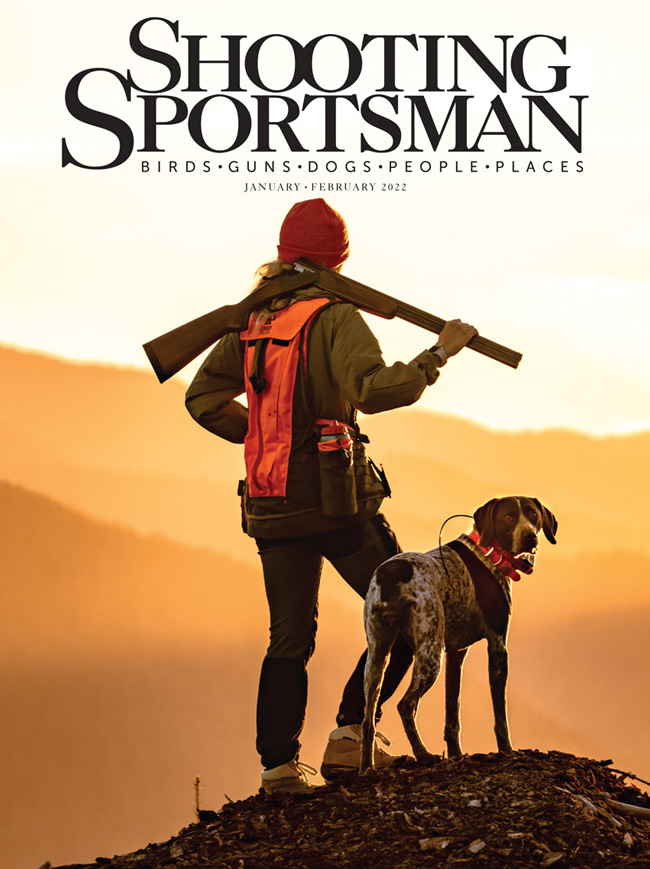

Text and photos by Matthew Hardinge

The sound of tumbling rocks echoed through the dense fog, the force of gravity causing the only movement on the mountain that morning. The hillside was steep, the earth loose, sliding and tumbling away beneath my boots as I made my way across the mountainside. I could be forgiven for thinking it felt a lot like chukar hunting; however, this was a different pursuit altogether. The terrain certainly was the same as in chukar country—the mountain climbing straight up and, if you fell, straight down. The gradient, however, was not the only challenge, as I was entangled in thick brush that resembled that in the grouse woods.

The fog was thick, impairing visibility. The sound of the dogs moving through the scree-laden hillside was the only reminder that I wasn’t on this quest alone. The click-clack of rocks ahead became slower; the dogs’ movement becoming more methodical until it eventually stopped, triggering the chime on the GPS to ring out through the fog. The tone immediately released adrenaline into my bloodstream, and my heart beat harder as I moved in the dogs’ direction. I slipped and stumbled across the loose, wet rock as I tried to get a visual on the point.

Suddenly there came the burst of wingbeats through the fog on my left, and then on my right; and as I got closer, more faded off in the distance. I hurried in hopes that at least one bird remained, and finally my older dog Ceder’s tail, vibrating vigorously, came into sight. Both of my dogs were still on point. To my disappointment, however, no quarry remained. They had eluded us, as if they’d known their fate had they stayed. It seemed that just as quickly as we had found them, they’d disappeared into the fog without a trace. No birds in the bag and not even the smell of fresh gunpowder. Nary a glimpse of the beautiful banded feathers or handsome topknots. Nothing.

On my trip to the same mountain two weeks prior, I had navigated the steep country in between torrential rainstorms. That day I had managed to scratch down four young mountain quail and a blue grouse in a relatively short time. That had been my first hunt of the season, and if I had shot straighter, I probably would have had a limit. The birds had been holding beautifully that morning, offering plenty of opportunities—albeit in incredibly dense cover. The dogwork had been superb and just where we’d left off the previous season.

This time I had returned with high hopes, looking to improve on the previous effort and bag some more-mature birds. I ended up driving off the mountain with my tail between my legs, an empty vest and disappointed dogs. It’s funny how quickly things change as soon as you think you have it all figured out. I was disappointed that my scramble across the dark, wet mountain hadn’t provided, but I had to remind myself that we were chasing the most elusive native upland gamebird—which is, after all, what makes the mountain quail so special.

The pursuit of mountain quail (affectionately known by bird nerds as Oreortyx pictus) is not for the faint of heart. The terrain is challenging, the cover thick and the shooting opportunities exciting, but the only thing about the birds that is predictable is their unpredictability. Often they hold so tight that you almost step on them; other times they run uphill or rocket off in the distance just out of range, leaving behind nothing but confusion. One day they are like a well-trained Labrador, eager to please. The next they turn into Houdini himself, leaving the best hunters scratching their heads and the most-experienced dogs chasing their tails.

Their behavior isn’t the only thing with such variance, however. Mountain quail are also tough, adaptable birds that can call a variety of places home—even the barren cheatgrass-covered chukar hills. I have been lucky to spend many days chasing these beautiful birds through the mountains. Most of my time has been spent in the Sierra Nevada and Cascade ranges in California and Oregon, but I also have hunted in Nevada—even getting a mixed bag with chukar. The mountain quail’s native range starts in Washington State and extends down the West Coast, with sunny Baja, Mexico, its terminus. Despite such a large range, the best populations are found in Southwestern Oregon and Northern California, an incredibly beautiful area that requires no arm twisting to explore.

The Sierras are home to not only North America’s largest quail but also the tallest peak in the Lower 48: Mount Whitney, which stands 14,505 feet. I’ve been to Whitney’s summit, and you can relax knowing that this is not where you need to go to find these birds. Chasing mountain quail in California’s Sierra Nevadas involves navigating thick manzanita bushes, climbing huge granite boulders and struggling up steep and sandy hills. The seasons open early and, as a result, temperatures can be incredibly hot, sometimes reaching triple digits. One benefit of hunting the early season is the birds’ dependence on water, which makes narrowing down places to search a lot easier. If you’re in mountain quail habitat, starting your search around perennial water is a smart bet, both for locating birds and so you don’t have to carry as much water for the dogs. The terrain here also can be rocky, and often you’ll find yourself navigating between rock formations. The granite rocks are sharp and, while your boots may grip them beautifully, they can tear up a dog’s paws quickly—especially with dogs not accustomed to the sharp rocks we face out West.

The Sierras are a huge expanse of habitat, and the thought of looking for birds there can be intimidating to an outsider. Luckily the elevations are not the highest, usually topping out around 10,000 feet. That said, mountain quail are more commonly found in the zone between the tall evergreens and the sagebrush-dominant landscape below. In California this habitat often is called chaparral, and it is largely dominated by oak, manzanita, buckbrush and sagebrush. Old-growth chaparral is a mountain quail hunter’s worst nightmare; it can be so dense that it becomes impenetrable to both man and dog, offering the birds perfect protection from predators. I have been in situations where an entire covey has hidden inside a thicket, refusing to flush and simply moving from one side to the other as my dogs and I have attempted to get them to fly. My love of pursuing these birds is so strong and I have found these situations so frustrating that I decided to add another dog to my string to hunt this exact type of cover: an English cocker spaniel. I didn’t need another dog, nor did I need to test the strength of my marriage, but I did need another arrow in my quiver in my continuing quest to outsmart mountain quail.

Just north of the Sierras is Mount Shasta, which marks the southern tip of the Cascades, a volcanic mountain range that extends from Northern California to British Columbia. This range is unlike any other in the US, as it is dominated by snowcapped volcanoes that rise high above the timber, setting the scene for the entire Pacific Northwest. Many of these volcanoes are still active, and trips to the summits of active peaks will reveal geological phenomena such as fumaroles spewing volcanic gas into the sky. But wait; don’t pack the climbing ropes and gas masks just yet—there are no birds up there either. Just like in the Sierras, mountain quail prefer the transition zones between the timber and the foothills.

Oregon’s Cascades are a beautiful place to chase these elusive birds and, active volcanoes aside, they offer their own unique challenges. Here the granite of California is replaced by Oregon’s equally sharp volcanic rock. Rarely is there a place to trust your next step, as black, crumbly basalt dominates the landscape, creating large fields of scree and offering mountain quail yet another advantage. In contrast to the Sierras, the Cascades receive significantly more rainfall, so wet, muddy conditions should be expected—and the chances of being engulfed in fog are common. Because of the abundance of rainfall, birds won’t be as concentrated around water sources as they are in drier areas. Keeping this in mind, it’s best to look for suitable habitat such as burn scars and old clearcut zones that stand out amongst the tall evergreens and offer the thick, low-lying brush that mountain quail need to feel safe.

The rewards are far greater if you have to work hard to achieve them.

The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife states on its website that your best bet is to drive through the mountains on logging roads until you see birds; however, I wouldn’t bet your whole hunting trip on a game of chance. Hunting mountain quail means you’re already working against the grain, so it’s best to control what you can and be methodical about your scouting efforts. In Oregon the scouting is easier, as burns and clearcuts are obvious on satellite imagery and onX. In California I look for areas as I’m driving, taking notes about spots that have favorable cover and then turning my focus to perennial water nearby. With a little bit of work online, you can cut down the miles of scouting on the ground and make sure your time is better spent hunting rather than exploring.

While I haven’t painted the best picture when it comes to hunting mountain quail, you can be sure that the shooting opportunities are some of the most exciting in the uplands. Walking through the steep terrain, busting through thick brush and sliding across rocks only to hear the birds call through the fog and the sound of wingbeats fading in the distance are what makes these quail so frustrating—yet desirable—to so many. As with most things in life, the rewards are far greater if you have to work hard to achieve them. At times it can feel as if you’re chasing ghosts or following shadows through the mountains, but you can be sure that when you connect on your first mountain quail, it will be a moment you won’t soon forget.

Matt Hardinge lives in Central Oregon with his wife, daughter, five cows, four chickens and three bird dogs. His day job is in marketing, but his writing has appeared in Outdoor Life, Modern Huntsman, Project Upland, Pheasants Forever Journal and Tread Magazine. When not at his desk, his favorite things to do are climb mountains and chase chukars behind his German wirehaired pointers, Cederberg and Summit.