Conservation creates a Carolina Lowcountry haven

FLORA AND FAUNA pay the ultimate price for the acres we pave and plow, and we seldom calculate the cost in its entirety until long after the ink dries upon a contract. Not all development is bad, but when weighed against the sacrifices we demand from the resource, places where there’s little difference between the way things were and the way things are seem more precious than another strip mall.

As bulldozers and backhoes churn the earth across South Carolina’s Lowcountry, at the confluence of the Ashepoo, Combahee and Edisto rivers—an area known as the ACE Basin—many of the roads are still gravel and most of the businesses are still small. Around these parts, boat captains read the tides and know every bend of the saltcreeks turn by turn, steering their weathered trawlers between corridors of cordgrass until they reach open water. Brackish rivulets finger off the main creeks like blood vessels, carrying creatures to their favorite near-shore nooks and crannies. Just before the Ides of March, wild turkeys gobble from the boughs of hardwood trees anchored by thick roots in the swampy bottoms, and during the sultry summer months fly-fishermen whip their rods back and forth from the bows of skiffs until just the right moment of release into a school of redfish. Wingshooting starts the first week of September, when mourning doves dive into withered sunflowers, and by month’s end falling temperatures push flights of blue-winged teal into flooded fields of rice and corn. Wood ducks, wigeon and gadwalls arrive just in time for holiday feasts and festivities, and hunting waterfowl over such splendor is an opportunity never to be missed.

THE AIR FELT balmy during the first two weeks of December, and a light fleece was all it took to stay comfortable. It didn’t feel like waterfowling weather, but my friend Philip Matthews invited me for a hunt at his uncle’s place in the ACE Basin near Edisto Island, South Carolina. “We’ve got so many wood ducks that we won’t have enough food for the migration,” he said. “I need some help down here.”

A glance at my calendar showed no prior obligations. “Sign me up,” I said. “I’ll see you in a couple hours.”

Night fell before my arrival, and I chose a rack in the bunkhouse while Philip stoked the fire inside a pit on the patio. He eclipsed part of the flame with a steel plate, and by the time I joined him a bushel of oysters hissed atop the hot metal from beneath a dripping croker sack. My eyes tracked the wafting smoke and steam upward as they joined patches of cumulus clouds in the night sky. Gaps in the pillowy blanket revealed bright stars burning in their proper places upon the celestial plane, but a cold beer Philip placed in my hand brought my attention back to Earth. A pair of headlights weaved around an alley of oaks bedecked in Spanish moss, and our friends Lucy Mahon and Margaret Ellen Pender arrived just as we shoveled the first batch of oysters off the fire. We shucked and grazed through the first batch, chasing their salty succulence with sips of bourbon and beer. We pulled a second batch from the fire and slowed our pace of consumption, then shucked and bagged whatever couldn’t be finished. We fueled the fire one log at a time to keep it alive, but fatigue overwhelmed us soon after midnight and we abandoned the flames in favor of a few hours’ rest.

We watched ’em land for a while once we got our three.

Five-thirty felt as though it arrived as soon as my eyes closed. We girded ourselves with waders, guns and gear before piling onto an ATV and heading to the impoundment with Philip’s Drahthaar, Ellie, and Lucy’s Boykin spaniel, Mac, running just ahead of us. We discussed strategy, and Philip suggested we cover each quadrant of the impoundment by splitting our group. “You’ll hear them first,” he said. “Then they’ll fly over one of these flooded fields. It’s a coin toss as to which they’ll choose first, but the shooting will move them between the two. Just be ready, because they’re never late; and they’ll hang around for a while, so don’t feel rushed.”

He sent me to the southwest corner of the flooded corn, and I settled into position. As darkness gave way to twilight, the sun’s ascent revealed a row of trees still wearing some foliage. Since winter winds hadn’t bared their branches, I positioned myself beneath the canopy for concealment and waited. Across the levee, I heard the first flights of wood ducks squealing and shrieking like a tribe of monkeys in the Costa Rican jungle. It seemed they’d chosen to fly above the other impoundment, but a flight of four appeared above my head and I caught a fleeting glimpse of them between the yellowing leaves.

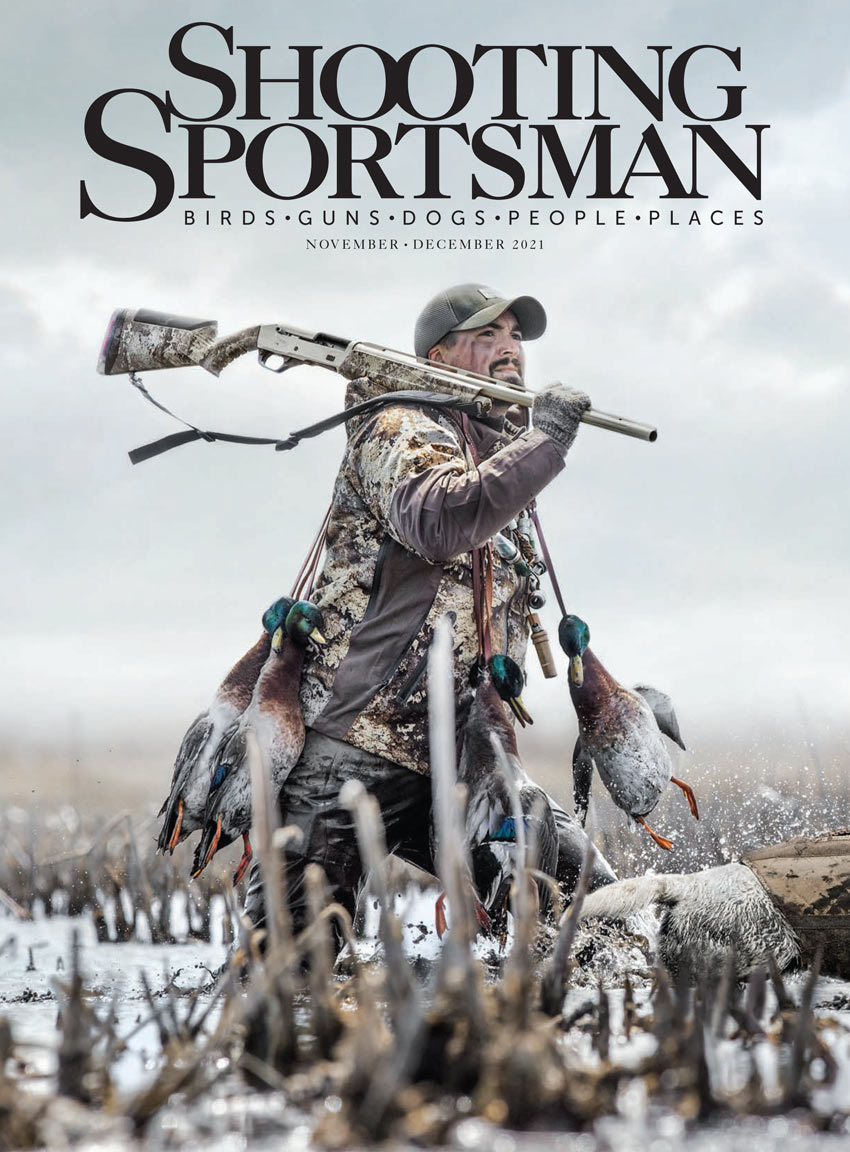

With the wood ducks circling, the seconds seemed to pass like minutes before legal shooting time. When my watch ticked the last torturous second past 6:28 AM, I planted my boots and wrapped my off-hand around the forend of my shotgun. The ducks swarming my blind disappeared, but an opening salvo from across the levee initiated the hunt and sent a squadron soaring over me at three-o’clock high. A clear shot presented itself, and I mounted and emptied my Beretta autoloader but failed to connect. Another pair passed overhead while I fed ammunition into my gun. They squealed and circled and committed to landing, and my second shot tumbled one just above the cornstalks. It fell heavy like a stone, and after several minutes of calm, I waded from the wood line, sploshing through the stalks and husks and water to retrieve my mark. I found the wood duck drake belly-up atop the water, and his beautiful plumage reminded me of the complex duality faced by all who honor the resource and its gifts—saddened that this beautiful creature met his end but relieved that a single cartridge delivered the coup de grâce. One life ended to sustain another. I carried him back to the wood line and looped his legs into my game strap before tying it around a low branch.

During a moment of inattention, the silhouettes of three more wood ducks flying overhead reflected back at me in the water. I gazed up at the skies to find them but didn’t get a visual until they’d flown out of range. Several more wood duck flights passed over—and several more cartridges were spent—before a single crossed the levee and presented a shot like a high driven pheasant. As the wood duck closed in, I shouldered my gun, led it and fired. The duck spiraled and splashed into the water almost close enough to catch had my hands been empty. I added the second drake to my game strap, and after a long cessation of shooting, I heard the engine of the ATV signal the conclusion of our hunt. Philip and his wife, Hanna, motored over, and I emptied my chamber and collected the cartridge hulls bobbing in the water. A wooden staircase aided my ascent of the levee berm and, before I completed the climb, Philip asked, “How many’d you get?”

“Not nearly enough to account for all that shooting,” I replied, “but I managed a pair.” Lucy and Margaret Ellen ambled over from across the levee with a limit of wood ducks on each of their game straps. “We watched ’em land for a while once we got our three,” Margaret Ellen said. We loaded the ATV with our guns and game, and while everyone piled aboard, I felt inspired to walk back to the bunkhouse at a leisurely pace. The dark of night had denied me a proper introduction to this lowcountry vista, and I intended to make up for it.

Sunrise had supplanted twilight, and as the sun burned behind a blanket of blue-gray clouds, it smeared streaks of warm yellow hues across the horizon that melted into the marsh. While I strolled along the levee, my mind wandered through the places and spaces I’d inhabited during my life, and I recognized that while I was grateful for my Louisiana roots, the rest of me had grown better once planted in South Carolina soil. This place grabbed my soul, and as I explored more of it, particular locales within the ACE Basin spoke loudest to me. But in an era before my time, the majesty and culture of this region had come under threat by monied men who’d stood to gain a king’s ransom from its destruction. They’d envisioned long stretches of beach clubs and attractions that would sprawl over every feasible site between Charleston and Beaufort. In 1988 renowned conservationists, government agencies and concerned citizens mobilized the ACE Basin Task Force and told them they would go no further. Federal and state wildlife agencies secured portions of the ACE Basin for the public good, while private interests holding grand swaths of property entered into strict conservation easements. These private landowners viewed themselves as custodians of the resource rather than owners of it—choosing legacy in lieu of profit—and they allied themselves with organizations such as Ducks Unlimited, The Nature Conservancy and several smaller easement programs. This collaborative patchwork of private properties with restrictive easements created a fortified barrier to irresponsible development, and it ensured most of the area would remain habitable for wildlife in perpetuity. When Philip’s uncle purchased the place we hunted, air-conditioned structures on the property were limited to 5,000 square feet and more than 75 percent of the land had to be dedicated to management for wildlife habitat. He built the bunkhouse and other outbuildings, planted fields in food sources for whitetail deer and wild turkeys, sowed sunflowers for doves and dug impoundment ponds for waterfowl. These days when the time is right, they cut and burn as needed to conserve their corner of creation.

Before I made it back to the bunkhouse, Philip and Lucy had started breakfast while Hanna and Margaret Ellen had concocted Bloody Marys. Venison sausage patties popped and sizzled in a cast-iron skillet while their savory aroma wafted around the kitchen. Lucy fetched a pot of salt water from the creek and brought it to a boil before adding a couple cups of local grits milled a few miles away. She cooked them low and slow, thickening them with a block of Brie from our charcuterie the night before. Philip plated the venison patties and broke a half-dozen eggs into the hot skillet, sopping up the sausage flavors as he stirred them to a scramble. We heaped the creamy grits and eggs and sausage onto our plates and seated ourselves in a row of Adirondack chairs overlooking the marsh. Between bites of breakfast and swigs of Bloody Marys, our conversation drifted toward aspirations we held for our golden years; and though a piece of this ground appealed to us all, Philip assured us it was not for sale. “That’s just as well,” I said. “There’s no emergency care within half an hour for somebody elderly. If something happened and you needed a doc, you’d better make it to Walterboro or Charleston by land or Beaufort by boat.”

“Well,” Lucy said as she drained her Bloody Mary, “as far as I’m concerned, it’d be good enough to die here.”

DU’s Conservation Easements

Conservation is a key component of sporting life. Without it, the resource dwindles to a point beyond recovery. Ducks Unlimited has been on the forefront of conservation efforts for the past 80 years, and as of 2021, the organization along with a network of members, donors and volunteers has protected more than 15 million acres across North America. These protected areas not only sustain waterfowl populations, but they also ensure the survival of other species, including humans.

One of the avenues used by DU to meet conservation needs has been its easement program. These legal agreements, entered into voluntarily by landowners, protect properties from development for a fixed number of years or in perpetuity. When several neighboring proprieties enter into these agreements, it creates a shield against overdevelopment and encroachment. Unlike the practice of land preservation, land conservation requires intense management in order to provide a net benefit for the resource. Conservation easements stipulate best management practices tailored to the property and assign a conservator to visit the property for ensuring these practices are being followed.

As of 2017, Ducks Unlimited in South Carolina had permanently protected more than 127,000 acres—to include the ACE Basin—under its conservation-easement program. The enormous success since the program’s inception, in 1989, has grown into the Lowcountry Initiative and provided a springboard for launching other DU conservation-easement initiatives across the US. For more information about DU’s conservation-easement program, visit ducks.org and search for “conservation easement program.” You also can find out how to volunteer with a local chapter and become more involved.

Oliver Hartner is a South Carolina-based writer covering sporting-life interests. His work has appeared in Covey Rise, Quail Forever Journal, USA Today Hunt & Fish and South Carolina Wildlife. He serves on the South Carolina State Committee of Ducks Unlimited as its secretary.

Buy This Issue!