Photographs by Simon Buck

It was July in Norfolk, and Mark Fitzer stood in a sun-bleached field of wheat and pointed to a clump of trees: the Scarborough Clump. “It’s where driven shooting began,” said Fitzer, who is the head keeper at Holkham, a 25,000-acre estate that’s hailed as driven shooting’s birthplace in Britain. He was showing me the estate’s historic coverts, which in Queen Victoria’s day produced shooting so fine that an envious Edward VII, then Prince of Wales, adopted its gamekeeping techniques so as not to be outdone at Sandringham.

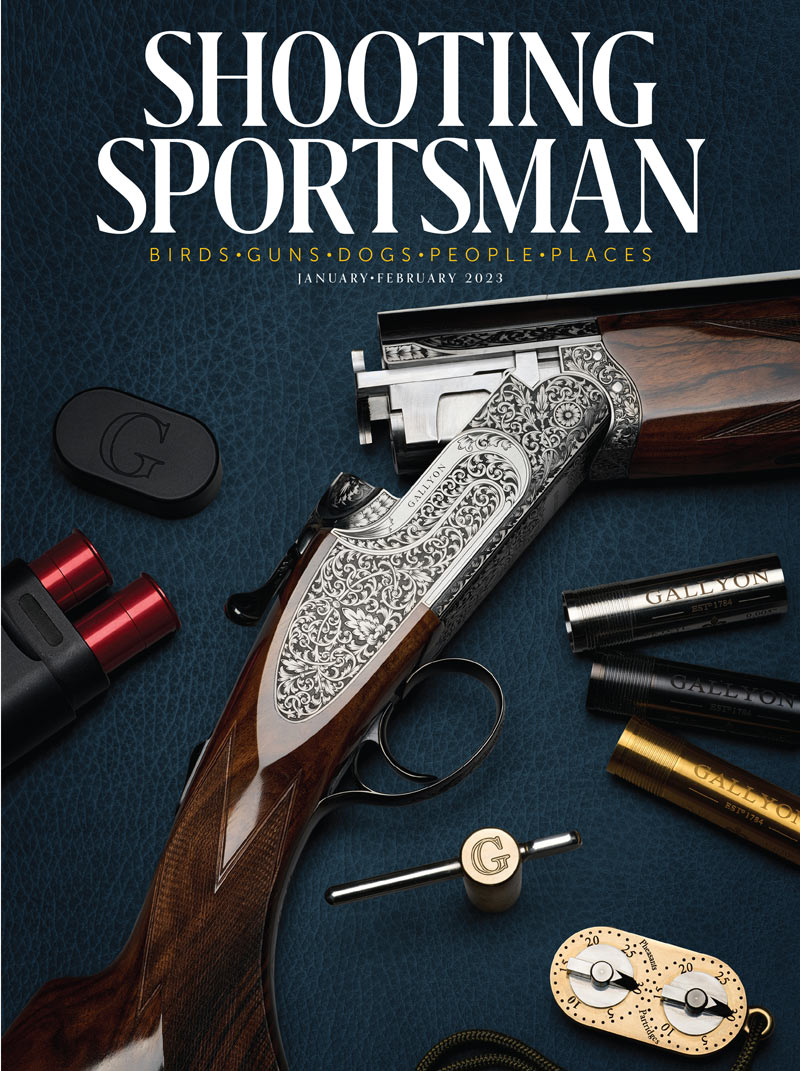

Later, as the sun dropped and the temperatures with it, I joined Fitzer in the Palladian grandeur of Holkham Hall, where his boss, Thomas Edward Coke, the 8th Earl of Leicester, was hosting a party to debut a new range of over/unders—driven-game guns made by Gallyon Gun & Rifle Makers, Ltd. Not coincidentally, one of the guns, the engraved sideplated model, is named the Holkham.

William Gallyon started making guns in Cambridge in 1784, about the same time Thomas William Coke, the 1st Earl of Leicester, began planting the trees that today comprise the Scarborough Clump. Gallyon has since made or sold some 26,000 guns, rifles and pistols, earning several coveted Royal warrants along the way while staying in family hands for six generations. Gallyon’s new guns, however, are unlike any that have come before.

If driven shooting, as inaugurated at Holkham, sparked innovation in 19th Century British gunmaking, then trends and emerging strictures in the 21st are redefining the modern game gun. Birds in the UK are, in general, driven over shooters at greater height than ever, accelerating demand for cartridges with faster and larger payloads—loads ill-suited for vintage game guns that by configuration (light weight) and metallurgy (mild steel) weren’t made for the attendant pressures and recoil. Craftsmen skilled enough to keep classic guns running are growing scarce. Draconian restrictions on lead shot loom, as Britain’s regulatory Health and Safety Executive has floated proposals to ban lead for game and target shooting within about a year. In the UK shotshell makers are scrambling; effective and affordable “soft” nontoxic solutions may become available, but that remains to be seen. For many the future looks hard, heavy and hot—that is to say: steel-shot cartridges, amply loaded, launched at high velocities.

Even before the lead-shot controversy reached crescendo, Britain’s side-by-side market had for decades given ground to modern over/unders. At Holkham I met Marc Brown, gunroom manager for Bettws Hall, which runs six commercial driven-shooting estates. “At Bettws,” Brown explained, “I can confidently say that at least 95 percent of the shotguns that come through our doors are over/unders, and 80 percent are 12s.” The vast majority of shooters traveling to Bettws are British, but most will not bear arms built in Britain. Gallyon’s new owners hope to change that.

In 2018 Adam Anthony, a former City of London financier, and Richard Hefford-Hobbs bought Gallyon & Sons from Richard Gallyon (who at 79 remains the company’s brand ambassador). One year later they reincorporated the firm in St. Neots, near Cambridge, as Gallyon Gun & Rifle Makers, Ltd., and based it in Falcon House, close to Cambridge Precision, Ltd. (CPL), a precision-engineering firm that Hefford-Hobbs started in 1994. The goal: to design and manufacture new O/Us entirely in-house to meet the evolving challenges confronting 21st Century shooters.

The guns would be graceful with understated aesthetics, so that they would appeal to British sensibilities, and they would handle well, be utterly reliable, be perfectly regulated and be “future proofed” for high-performance hard nontoxics. And, hardly least of all, they would come in not at the prices of best London sidelocks but close to those of the upscale-but-accessible imported O/Us that dominated the British market—the market Gallyon intends to conquer.

Jonathan Young, Gallyon’s marketing manager, introduced me to the project when he met me at Heathrow a couple of days before the Holkham unveiling and drove us north to Cambridge. For almost 30 years Young was editor in chief of The Field, the grand dame of British sporting magazines and certainly the most influential and aristocratic. He is an icon in English sporting circles, and I suggested that he probably shot matched sidelocks from London’s West End. “I currently shoot a pair of Blasers,” he said. “They’re very nicely balanced, reasonably priced and they always work.”

Young has decidedly non-romantic notions about gun embellishment—a sentiment expressed perhaps most pungently by iconoclastic Austrian architect Adolf Loos, who in 1910 proclaimed: “The evolution of culture marches with the elimination of ornament from useful objects.” Or as Young told me: “Handsome is as handsome does.” Young says he’s “a hardcore shooting boy” and that he joined Gallyon because he shared the new owners’ vision to build performance shotguns from the get-go—guns sturdy as a Clydesdale yet lively in the hands, with intrinsic lines thoroughbred enough to stand without engraving.

That’s exactly the gun Gallyon’s directors showed me in the boardroom at CPL. Adam Anthony, who steers Gallyon’s commercial operations, pulled a prototype Cambridge model from a slip. It was sleek and handsome with an unembellished scalloped-back action and stocked with a long, lean forend and a racy-looking buttstock with swept semi-pistol grip. “That,” I blurted after a good long stare, “looks like an English gun.” Yet it appeared nothing like a Boss or a Woodward, the classic London O/Us whose aesthetics are widely imitated and are now virtually archetypes of form. The Cambridge looked its own beastie—but as British and elegant as a finely formed Chippendale chair.

Anthony handed it over, and I guessed the weight. “About 7-12 pounds?”

Nope: “A fraction over 8.” Tick box one for superb balance and weight distribution, which made the gun feel lighter than it was. The underside of the action was smooth; there was no notch (or “gash”), so common on O/Us. “We engineered that out.” The toplever worked smoothly; so, too, the safety. I didn’t need a pull gauge to tell the Cambridge had a superb single trigger—free of creep, competition-crisp, light but not too light. “Three-and-a-half pounds each,” Anthony said.

When I opened the gun and the barrels dropped, they held firmly at the bottom. There was no “bounce”—the rebound you feel on many guns, even on expensive ones. The ejectors were expertly regulated, and snap caps landed within an inch or two of each other. What I recall best, though, was the quiet, solid confidence-inspiring click and the feeling in my hands as the Cambridge closed and its bolts went home. I’ve covered fine guns and gunmakers for more than 30 years, and the O/U that came closest to that sound and feel was—dare I say—a Fabbri. That Italian masterpiece starts around $150,000 unengraved; the Cambridge begins at £18,950 (about $21,750), with an engraved version at £23,950 ($27,450) and the Holkham at £28,950 ($33,200).

A Fabbri and a Gallyon are different designs serving different markets at decidedly different prices, but the thread that stitches their gunmaking philosophies together is the full-throated embrace of modern precision engineering.

Hefford-Hobbs—a Cambridge engineer, entrepreneur and philanthropist—wears many hats, including one as Chairman of the company he owns. CPL’s corporate mottos are: “Quality through Technology” and “Proud of Precision.” He showed me what that meant as he walked me through CPL’s grounds, which spread over 50,000 square feet in five buildings. Each brimmed with the latest CAD/CAM design and manufacturing simulation centers and CNC multi-axis milling and turning machines, manned by about 100 engineers, programmers and skilled technicians as well as “Cobots”—collaborative robots. CPL designs and makes complex components for corporations worldwide in the aerospace, nuclear energy, security, med-tech, forensics, audio and robotics fields. Among its many lofty accreditations is Fit for Nuclear (F4N) and the British Standards Institute’s ISO BSI 9100 (Aerospace, Space & Defense) accreditation, meaning it makes fully traceable (of known provenance) precision-manufactured parts measured in microns (one thousandth of a millimeter).

Gallyon’s research identified two sorts of customers: those who shot imported O/Us who’d relish a crack at an affordable English-made gun and traditionalists who’d been happy with older, lead-proofed British side-by-sides and now needed something modern but were reluctant to test O/U waters with “Johnny Foreigner.” Grabbing market share wouldn’t be easy. The best imports—mostly Italian and German—are time tested, competition proven and justifiably popular. (Ask Jonathan Young.) Traditionalists, on the other hand, expect lively handling and the “sweet” operation of a British artisan-made gun—refinements normally crafted in by hand that drive up costs exponentially. The solution was obvious; achieving it might not be. Gallyon had to design a qualitatively better gun than its competitors, and then manufacture it efficiently to keep its price competitive.

Design begins with two things: an intention to make something and a problem to surmount. Don Custerson would help Gallyon do both. Custerson is unique in the English gun trade: He earned a BA and MA in engineering in the early ’70s from the University of Cambridge and over the next 16 years developed cutting-edge machines to apply specialist coatings under high vacuum to metal surfaces, a process called Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD). He’d grown up with a passion for guns and rifles and started gunsmithing at home in his spare time, eventually becoming a part-time outworker to the best London trade. When the engineering firm he worked for was sold in 1989, he turned to full-time gunmaking and, eventually, to designing guns for clients—most recently the Stephen Grant O/U in 2017.

By the time Anthony and Hefford-Hobbs contacted Custerson in 2019, he was semi-retired. What appealed to him, however, was Gallyon’s insistence on performance over tradition when designing its gun, which allowed Custerson complete freedom to innovate with materials and build-methodologies and to harness CPL’s formidable design and manufacturing capabilities. “Gallyon’s requirement was simple,” Custerson told me. “Produce an O/U that was reliable, robust, handled well and was English in style, with no compromise in terms of reliability.”

Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) is an engineering process that identifies potential or existing design failures in complex systems—the failure modes. Studying the consequences of failure is effects analysis. Developed for the military, the objective is to ensure utter system reliability. Custerson used FMEA to analyze the competitors Gallyon had put in its sights and systematically tease apart their flaws—component by component, gun after gun. After the analysis, Custerson ensured that no failure modes were present within the new Gallyon gun design.

“Don has 50 years’ experience fixing many of the faults he found on his customers’ guns, both old and new,” Hefford-Hobbs explained. “Therefore, he has an extremely close relationship with failure modes. As our design was totally new—not a copy of any other design—our process ensured no known faults made it into the Gallyon.”

As purpose-built driven-game guns, Gallyons have initially launched as 12-gauges, but 20- and 16-gauges are on the way.

The house engraving specific to Gallyon—seen on the sideplated Holkham and the Cambridge Engraved—is based on the patterns of Christopher Dresser, a celebrated designer in Britain’s 19th Century Aesthetic movement. The lush, foliate patterns have been artfully adapted to the Holkham and the Cambridge Engraved. The engraving is part laser and part hand cut, except on the Holkham Deluxe, which is fully hand engraved and the priciest option at £39,950 (about $45,800).

Engraving adds beauty, but beneath it every Gallyon is built to the same design and exacting standards of precision and accuracy—the standards CPL applies when making components for jet engines, nuclear reactors and Formula One cars. Gallyon uses pre-hardened and tempered high-performance tool steels for its parts and actions and solid billets of chromium molybdenum steel for barrel tubes. All materials used within each Gallyon are fully traceable.

The Gallyon shotgun is a low-profile triggerplate design with rebounding locks powered by coil springs. The monoblock barrels mount on replaceable hinge pins in the action walls, and the draws in the action’s Boss-influenced recoil shoulders are also replaceable. It has an inertia-regulated, mechanical-change-over single trigger that is non-selective (the order in which barrels fire can be set at the factory). The interchangeable choke system—in stainless steel or titanium—is designed and manufactured in-house to handle the hardest nontoxic shot and comes with a range of performance coatings, if required.

A number of these elemental features can be found in other premium O/Us, but drill down in the Gallyon design and the attributes of the performance-first approach to gunmaking begin to surface. For example, the action and many components are surface-hardened by plasma nitriding, which makes them highly resistant to wear and fatigue. Unlike with traditional carburizing, this process creates no metal distortion. The components are then given a thin ceramic coating using the PVD process Custerson helped develop decades ago, making them virtually wear-proof and impervious to rust. This also functionally reduces friction in moving parts such as lockwork. One performance coating, “Gallyon Blue,” is used by the gunmaker. The action, forend and furniture also get the PVD treatment but with metal nitrides to color them—black, for example, or the gunmetal finish on the Cambridge I saw. Customers can select any number of different finish types and color combinations.

The firing pins, which are robust and made of tough stainless steel, are titanium-nitride coated to resist wear. It would take a lot to harm one.

The bolting arrangement looks similar to that on Beretta’s 680 Series guns, but Custerson designed the bolt to seat deeper in the barrel recesses when the gun is closed, and it’s machined in a “D” shape—the “D-bolt,” as Gallyon calls it—with the flat at the bottom to increase the bearing surfaces. The barrels drop far enough to provide a wide gape, which speeds reloading. On most O/Us this creates the unsightly “gash” on the action’s underside—but not on the Gallyon.

We’ve made the Gallyon to quality and performance standards to become an heirloom.

The ejector system is brilliant. Extractor heads grip cartridge rims with full 90-degree engagement for sure extraction and ejection, and when the gun is opened, they ride high to help removal by hand. Custerson designed an ejector stop (the “G-spring”) to dampen the shock on the extractors at the end of their travel as the empties kick out; conversely, the extractors retract fully just before the action closes, preventing the cartridge head from “wiping down” the breach face, which can cause incremental wear over the decades and shave off metal particles from the cartridge base that can then make their way into the lockwork. It also makes the gun smoother to close.

As mentioned, Gallyon uses monoblock barrels—as do almost all makers of modern O/Us—in part because convergence angles for barrel tubes can be accurately machined in. But the similarity with other makers ends there. Gallyon has patented an Inter-Rib System, a lightweight, one-piece, skeletonized barrel support 18 inches long that runs between the barrels. It is precision-machined with concave surfaces top and bottom to accurately match the profiles of the tubes that nestle along its length. Each side of the Inter-Rib facing right and left functions, in effect, as a side rib and replaces the two individual components. It is then bonded in place along its full length, effectively sealing off the barrel unit from corrosion-causing moisture. You could say it is “glued in place,” but that doesn’t do justice to the shock- and heat-resistant aerospace-grade adhesive that Gallyon employs—the same rigorously tested adhesive used in building Formula One racers and, as Hefford-Hobbs told me, “the jet you flew to England in.”

Gallyon also uses this adhesive to affix the top rib and to bond the tubes in the monoblock. Custerson profiled the barrel walls to provide strength where needed using high-performance steel and optimized the bores, forcing cones and choke design for hard shot. The barrels have 3" chambers, and the gun is proofed in London to CIP Superior Steel pressures. Depending on barrel length and preference, a Gallyon will weigh from 7½ pounds to just more than 8.

“With our design process,” Hefford-Hobbs said, “we’ve not looked at one thing; we’ve looked at lots of little things, and they’ve come together and made our gun significantly better.” And although England isn’t known for making guns at accessible prices, the Cambridge can be had for the price of many machine-engraved Continentals. How?

According to Custerson, it is not only possessing the best technology that influences price, but also how intelligently and efficiently that technology is employed. One example: From the start Custerson designed the Gallyon’s manufacture in a way that minimized the need for electrical discharge machining (EDM) and maximized milling. “EDM produces excellent results,” Custerson said, “but with several operations in sequence on various machines, the cost it incurs is high compared to completely machining a monoblock in only two operations on one of CPL’s state-of-the-art five-axis milling machines. With this in mind, I approached our design to enable almost all machining of parts to be milled.”

For all the tech, handicraft still has its place—in Hefford-Hobbs’ words, “at the user interface.” That means a custom stock with complimentary gunfitting, checkering by hand and a traditional oil finish. The trigger’s pull weight can be tuned, and the barrel tubes are lightly struck down by hand to remove any turning marks and are final-polished prior to a traditional blacking, which adds immeasurably to overall elegance.

I got in some all-too-brief user interface with the Cambridge on driven clay targets using Hull Cartridge’s Super Fast 27-gram No. 7½s. The trigger, ejectors, cocking and lock-up were as flawless as I had thought in Gallyon’s boardroom. Handling preferences are subjective and depend on the shooter and quarry, but I found the gun quick to the target and stable enough to stay there, but not so heavy and weight-forward to be unresponsive. For its intended application, I think it’s ideal. The Hull loads didn’t provide a definitive answer to how the gun delivers perceived recoil, but they were punchy enough—and I’m recoil sensitive. I was impressed. The recoil I felt came straight back with minimal barrel rise.

“We don’t classify the Gallyon a ‘best gun’ in the Victorian sense,” Anthony told me after we shot, “but we seek to define a new category, as it is a new gun for a new era. We like to think it’s ‘superlative.’

“We’ve made it to quality and performance standards to become an heirloom—an intergenerational object like grandad’s Purdey.”

When Lord Leicester unsheathes his new pair of guns ’round the Scarborough Clump this winter, he’ll have in his hands heirlooms that will have in ways more than one found a rightful home.