By Delbert Whitman Jr.

I was in my shop unpacking a fine little British boxlock that had just arrived. It was the epitome of an upland-bird gun: 20 bore, longish 30" barrels, straight grip, double triggers, dainty action body, the whole bit. It belonged to a longtime friend and client. He always had been a serious collector, much more so than a shooter or hunter.

The prior fall he had accepted an invitation to go grouse and woodcock hunting. By chance, the woodcock flights had been down, but the grouse had cooperated. That one day had been all it had taken: The sickness had taken hold fast and deep.

After that he had begun hunting as much as possible and quickly found that, regardless of how fine his guns were, his shooting skills left much to be desired. He had attended several shooting seminars, and then had had a gunfitting. He had decided not to have any of his collector pieces altered to fit (for obvious reasons) and instead had bought this fine little gun specifically with the intent to have it customized. After all, there are few things as lovely as a custom-fitted shotgun.

As I examined the stock dimensions his instructor had prescribed, I immediately noticed some discrepancies. Several of the dimensions simply did not make sense. In effect, the data was asking for a stock that would be physically impossible to produce, even if a new stock were made from scratch. I had seen this issue numerous times and had a good idea of what had caused the problems. A quick call to my friend confirmed my suspicions. The try-gun that had been used for the fitting had had a “universal joint”-type mechanism, to facilitate the articulation of the stock. Once confirmed, the issues with the faulty data eventually were remedied. If the prescribed data had been used for the stock alterations, much heartbreak would have ensued.

The “universal joint” is by far the most common used in try-guns. It is effectively two hinges joined together close to one another, one moving up and down to alter drop and the other moving left and right to alter cast-on and -off. It is the same design used on the drive shaft of most automobiles.

The reason this type of joint can be problematic is that it tends to be long and mounted far back in the wrist. With a real stock, the bend for cast and drop starts right behind the top and bottom tangs. I even have seen guns with the tangs bent in the direction of the cast. With a U-joint try-gun, the bend for cast and drop takes place much farther back in the wrist than it should. This abruptly increases the angle of the comb for both cast and drop. While it may not seem like this would matter much, it dramatically affects the accuracy of the fitting data. When you really think about what is trying to be accomplished, it is quite remarkable.

With nothing more than hand-eye coordination, we are attempting to hit erratically moving targets hurtling through the air at various speeds and distances with clouds of shot that also are flying through the air. It’s amazing that we ever hit anything at all. Little wonder then that in this game 1/16" can and does matter.

A skilled and experienced shooting instructor/gunfitter who also has a good working knowledge of stock design can take into account the discrepancies caused by a U-joint try-gun. He or she can translate the data to a real gunstock and the appropriate desired alterations. Unfortunately there are shockingly few gunfitters who really have this skill set.

After many years of dealing with this issue from the gunfitting and stockbending/alteration side, I decided to build a better mouse trap. I wanted to make a try-gun joint that would be shorter, pivot closer to the action and have the drop and cast movements come from the same spot. I wanted to create a try-gun that would generate measurements that would be directly applicable to a real gunstock.

The inspiration came to me, like many good things do, from my wife. She was at one time a surgical nurse who worked mainly on orthopedic cases. We were idly chatting about some of the space-age joint replacements that are now possible, and it hit me: Any joint that is multi-directional is most always spherical, like a hip joint—aka a ball-and-socket joint.

Ball-and-socket joints are compact, can move horizontally and vertically, and as an added benefit can rotate radially. They are also incredibly strong. I had the design in my head almost instantly. The process of figuring out how to actually manufacture such a joint proved to be the challenge; but when one has a milling machine, lathe and some patience, much is possible.

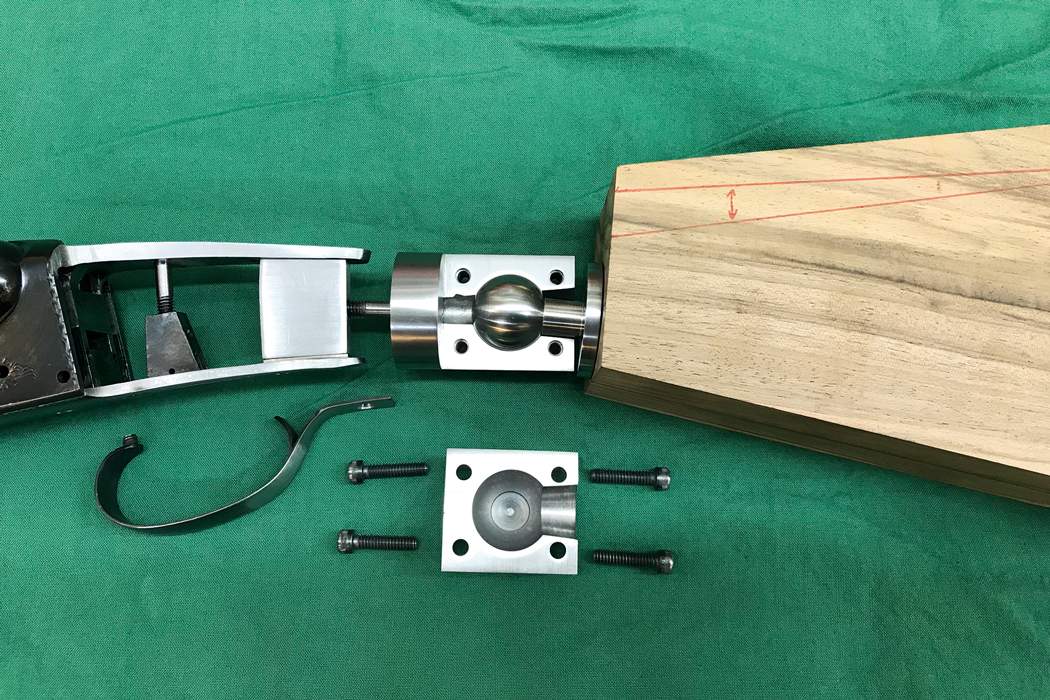

With reliability and durability being my main concerns, I chose a Miroku/Browning BSS-style gun for the try-gun build. This particular gun had double triggers as well. I machined the socket part of the mechanism out of case-hardened 8620. The ball and shaft that connect to the rear portion of the butt are high-tensile-strength 4140. All of the other fixtures are made of lightweight aircraft-grade aluminum. The screws that apply pressure to the clamping side of the joint are industrial-grade torx-head machine screws.

The method of attaching the joint to the action is also a weak spot of many try-guns. To remedy this, I installed a steel crossmember between the top and bottom tangs, and then installed a drawbolt like that used with most over/under shotguns. This proved to be a very strong method of attachment.

This joint affords a great deal of nearly universal movement. It is also vastly less complex than any other try-gun mechanism I have seen.

I am writing this several months after my new try-gun was completed. The design ended up having an extremely wide range of adjustability, with the length of pull being adjustable from 13" to 16½", drop at comb from 11/8" to 113/16", drop at heel from 1¼" to 27/8", and cast-off or -on 7/8". The buttplate can facilitate a 7/8" Monte Carlo as well. The degree of pitch and toe-in and -out adjustments are more than adequate. One of the nicest features of the design is that when the joint is locked in place, it is rock solid. It is also nice to know that the dimensions this try-gun gives are accurate and directly applicable to altering an existing stock or making a new custom stock.

I have done a half-dozen formal “at the plate” gunfittings, and all have gone very well. A gunfitting I did for friend Ron Boehme was a good example. Ron is the host of “The Hunting Dog Podcast” (thehuntingdogpodcast.com). He is an avid upland hunter and gundog enthusiast, and he is also tragically left-handed. Although he has been a wingshooter his whole life, he had never had a gunfitting or a gun fitted to him. He is of fairly average height and build, with a fairly muscled chest. I set up the try-gun with neutral cast and average drop and length of pull. I had him shoot several test patterns at the plate. His shots were slightly high and, as expected, well right of the mark. After only two more shooting sessions and some subtle adjustments to the try-gun, he was hitting dead center horizontally and the pattern was 60/40. That was just about ideal. He ended up needing 5/16" of cast-on at the heel and a bit more positive pitch than normal, due to his pectoral muscles. He left the shop with an accurate set of stock dimensions that he can use to have his existing guns fitted to him or to assess the fit of any guns he might consider purchasing.

It is my hope that this new kind of try-gun will help facilitate more accurate and realistic gunfitting data. After all, as mentioned: There are few things more pleasurable than shooting a well-fitted shotgun.